This blog really is about the shape of the universe.

When I was young, and I mean very young, still at Junior school, I would sometimes lie awake at night thinking about the size of the universe. Did the universe go on forever? But how could anything go on forever? But if not, how could it end? What would be at the end of the universe? Could it be a wall of some sort? But then would the wall go on forever? But if it didn’t, what would be beyond the wall? That is seven questions. Later I used to tell my children they were only allowed three questions at a time! To be fair to me, that was usually when they were repeating the same question – ‘why?’

This blog is getting rather long in the tooth. The reason is, instead of updating it, I have been concentrating on writing a book.

The Great Cosmological Coincidence; and the shape of the universe

Here is a synopsis of the book

(The book is intended for the interested layman. There is also a paper ‘An investigation into the empty universe’ for those with a more technical background, available at the following link. https://shapeoftheuniverse.blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/an-investigation-into-the-empty-universe-1.pdf)

In the early 20th century, Edwin Hubble and Vesto Slipher found that the light coming from all but a tiny fraction of the nearest galaxies was red shifted. The characteristic peaks in the spectra of the elements were moved to longer wavelengths compared to when they were measured here on earth. Hubble, and most other scientists at the time, assumed this red shift was due to the Doppler effect. The Doppler effect is responsible for the drop in the pitch of a train whistle or police car siren, as the source moves past you. And if we know the speed of light, which we do, we can use the Doppler effect to calculate the speed a galaxy is moving away from us, from its measured red shift.

Hubble then went on , using some very recent discoveries about a particular type of star, known as a Cepheid variable, to measure the distances to a number of galaxies. He was then able to develop the famous law, which bears his name, Hubble’s law, that the speed any galaxy is receding from us is proportional to its distance from us. The constant of proportionality is known as the Hubble constant. The great cosmological coincidence is this. Hubble’s law is surely correct and yet, at the cosmological scale, galactic red shift has nothing to do with the Doppler effect.

This book develops the most probable shape for our universe from the simplest of concepts. This shape then becomes a model of the universe. It is so simple it has been called Occam’s universe, after Occam’s razor, the idea that the simplest solutions are usually correct. . The model is then used to explain many features of the universe including why the Doppler effect is not responsible fo galactic red shift, and, later what is actually causing galactic red shift. The author feels sure this model must be correct. But even if it is not, you the reader read on and you will probably learn more about the universe than you thought possible.

If you are interested in this book, please contact john_a_hobson@outlook.com

Now, back to the blog

Many years later, more than I care to admit, I decided to revisit the question, starting almost entirely from scratch, and came up with a very satisfying solution, which answers all of the above questions and many more besides, including an interesting perspective on how it all got started. Furthermore, I believe it is accessible to the layman, with only a small amount of mathematics that many would have learned at school. As few of us will ever have the ability/opportunity to contemplate universes satisfying Einstein’s field equations, I believe it is extremely satisfying to contemplate the universe proposed here, many of whose properties may be correct, even if some are not.

One word of warning, despite answering all of the above questions, and many more, it appears my idea for the shape of the universe must be wrong. Something to do with allowed solutions to Einstein’s field equations. But I have decided to present it anyway. Perhaps it is not totally wrong, but only in some aspect. And it might get you, the reader, thinking more deeply about the universe than you believed possible.

I no longer think my ideas must be wrong (they may be though). Later in this piece, it is shown that the universe must get heavier as it expands. When this is factored in, I believe the model presented here will be compatible with general relativity although I would dearly love an expert to explore this further.

Just about all of the ideas I am presenting here, I have developed from scratch. It has been great fun. But I freely admit I have come to realize that most of the ideas here have been thought of by others before me.

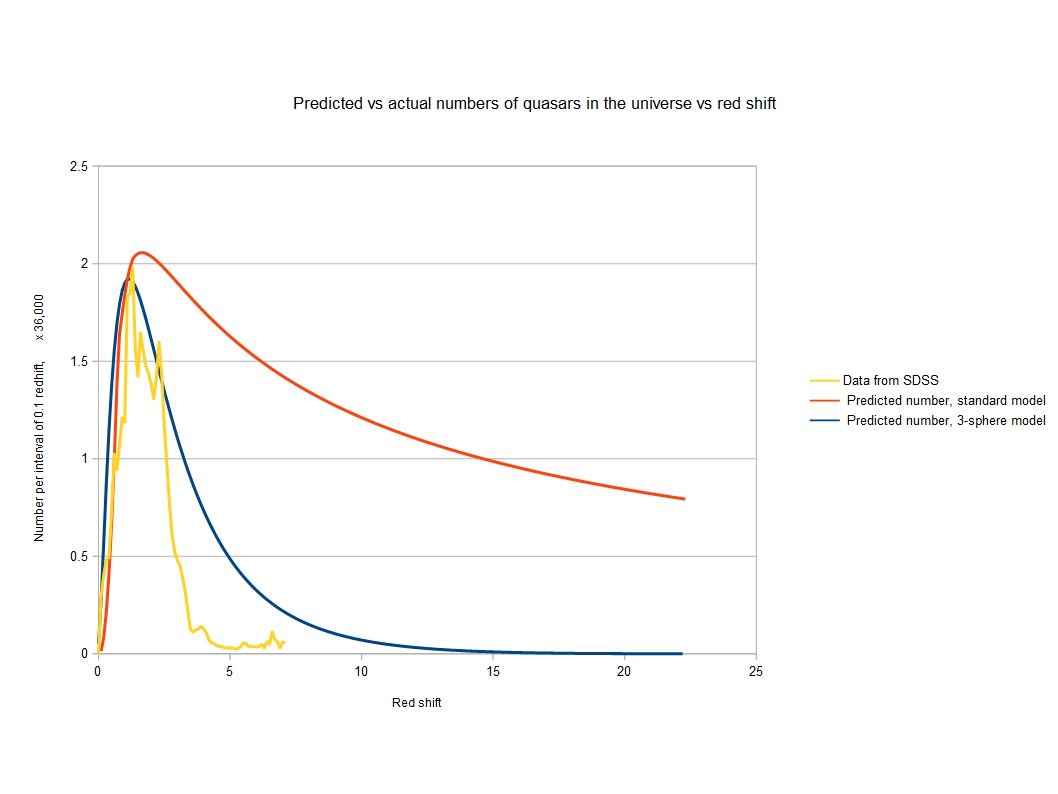

STOP PRESS. All of the time I have been developing this idea I have never found any way it can be tested against the more accepted model of an infinite flat universe. But now I think I have. This is given at the end of this blog.

So where to start. Well, here it is. The universe is a 3-sphere expanding at the speed of light. OK, perhaps that is not very rewarding. I suggest two possible solutions. One is to read the following article Shape of the universe 27 April 2018 (this is getting a little out of date now. In particular the section on the number of galaxies in view has been totally superseded by a study of quasars in view, near the end of this blog. This blog also contains some thoughts on black holes and dark matter that are not in the paper) . The other is to let me explain what a 3-sphere is and carry on from there.

Perhaps this is a good place for a quote;

“Nature is an infinite sphere of which the centre is everywhere and the circumference nowhere.” Blaise Pascal, Pensées (1670)

Pascal was a French mathematician of some note. You may have come across Pascal’s triangle while at school.

Actually I would rewrite this as follows

“Nature is a finite sphere of which the centre is nowhere and the circumference everywhere.”

In what follows, coloured text is there to provide a bit more detail, but can be safely ignored if you like.

Dimensions

In order to understand the nature of a 3-sphere, we need to think a bit about dimensions and the simplest objects you can have for any number of dimensions. A dimension is simply a direction in space. If we start with zero dimensions then the only object we can have is a point, since a point does not have any dimensions.

Here we have zero dimensions and the only possible object is a zero dimensional point.

Next, we move to 1 dimension.

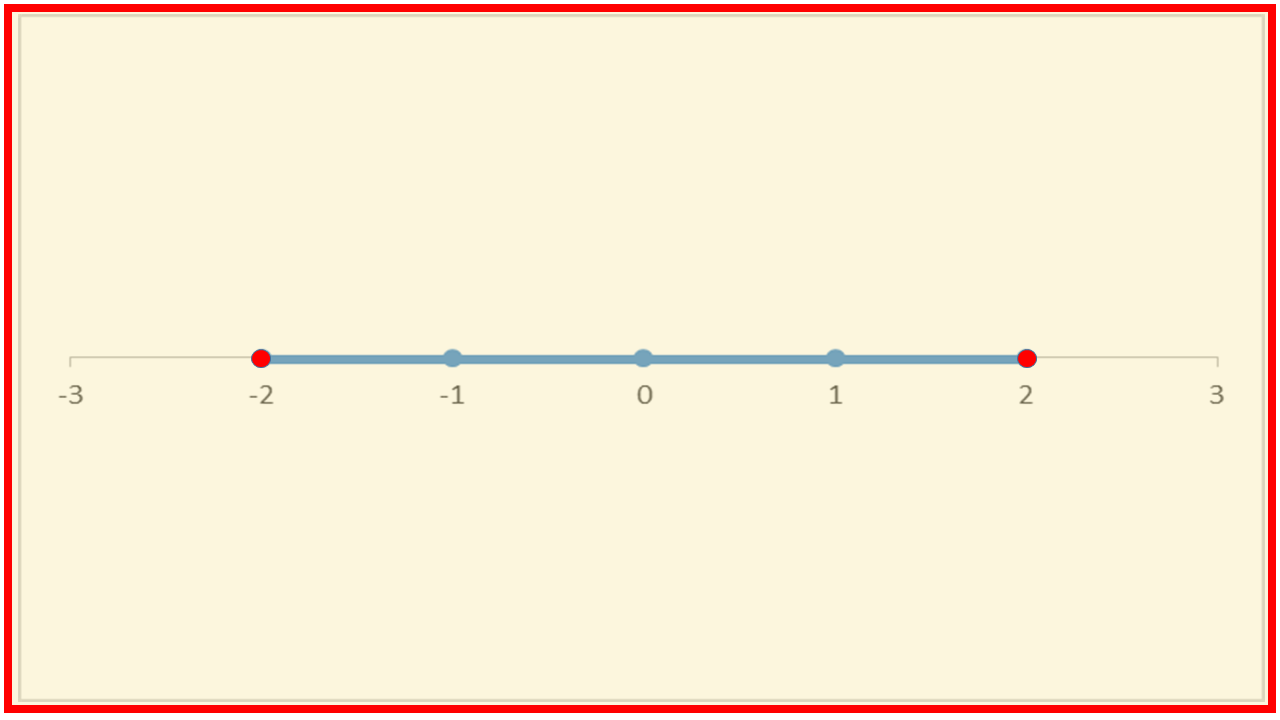

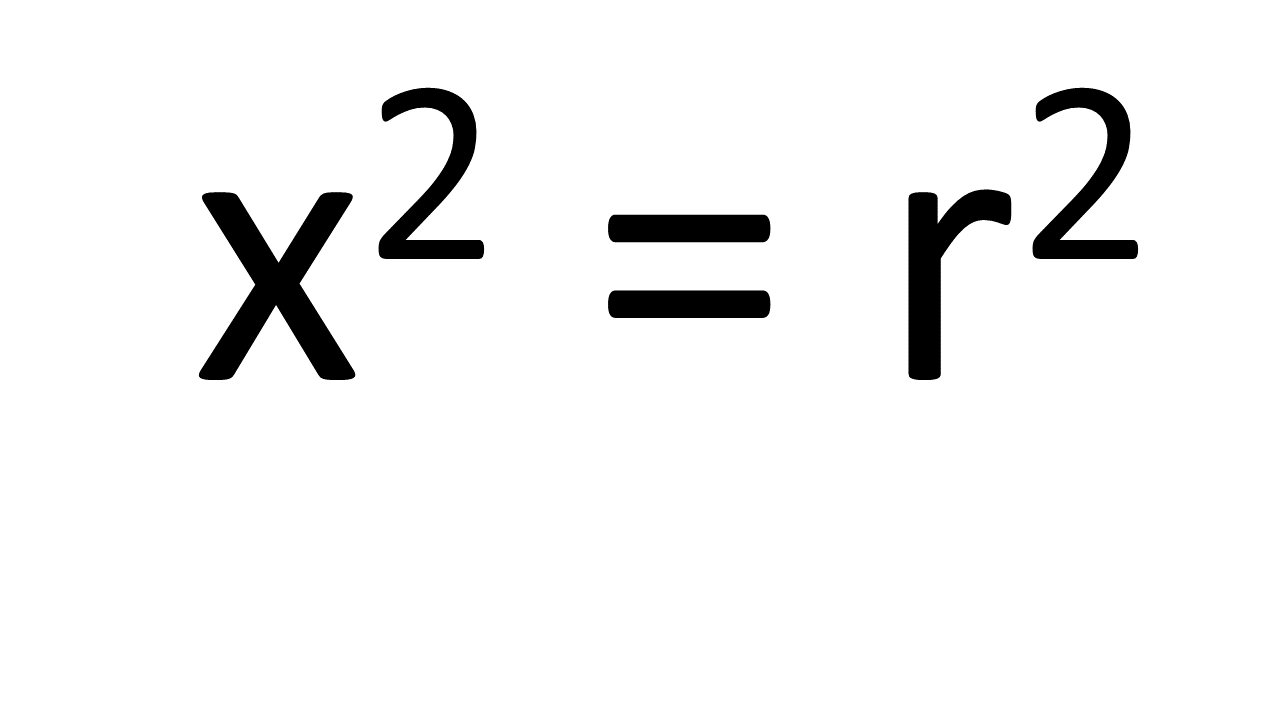

The simplest possible object in one dimension is a line, or more accurately a line segment. Here we see a line segment stretching from the point -2 to the point 2. Now for a little bit of maths. This line segment has the following equation;

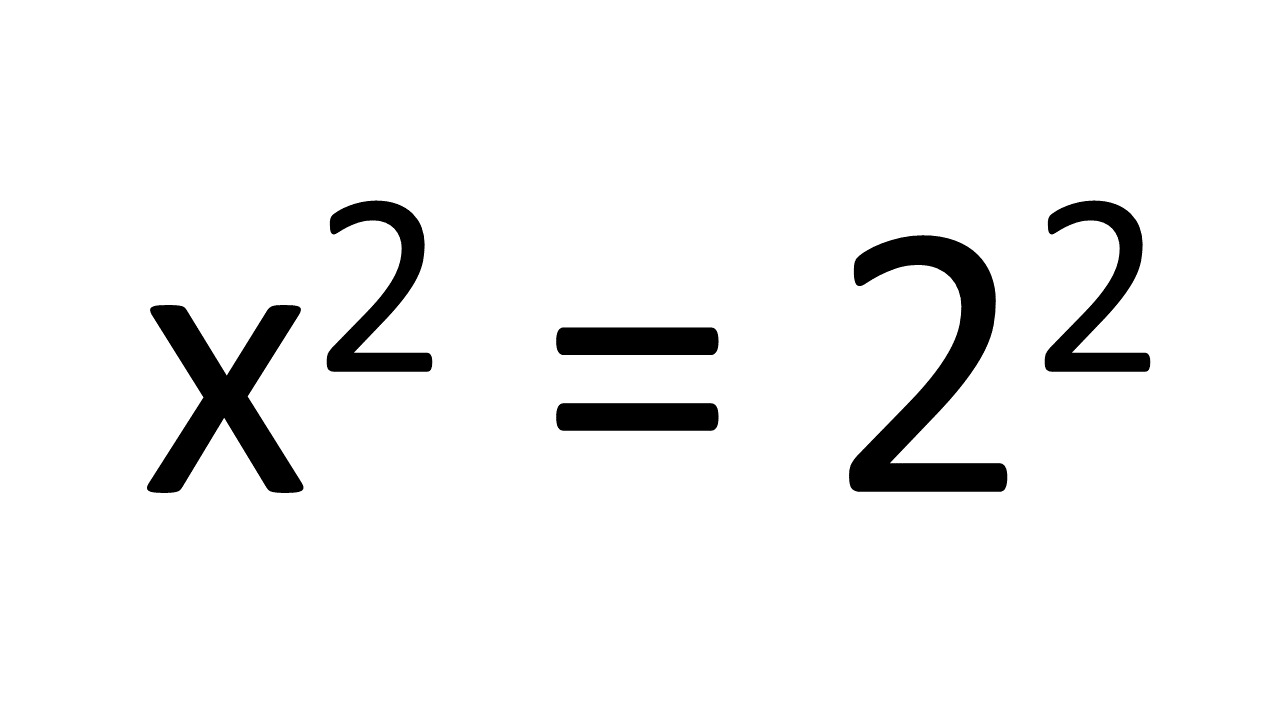

where r is the ‘radius’ of the line segment, that is 2. So we have

This may seem a little odd, but please bear with me. I am setting the scene for when we consider more dimensions. This equation has two solutions, x=2 or x=-2. The solutions are actually for the ends, or the boundary or even the surface, of the line segment. These two ends are points of zero dimension. So a one dimensional line segment has a zero dimensional boundary or surface. These two zero dimensional points are in fact a 0-sphere or zero-sphere. Note that the boundary or surface of an object has one less dimension than the object itself. Now when we move on to thinking about two dimensions I hope you will see why I am thinking this way.

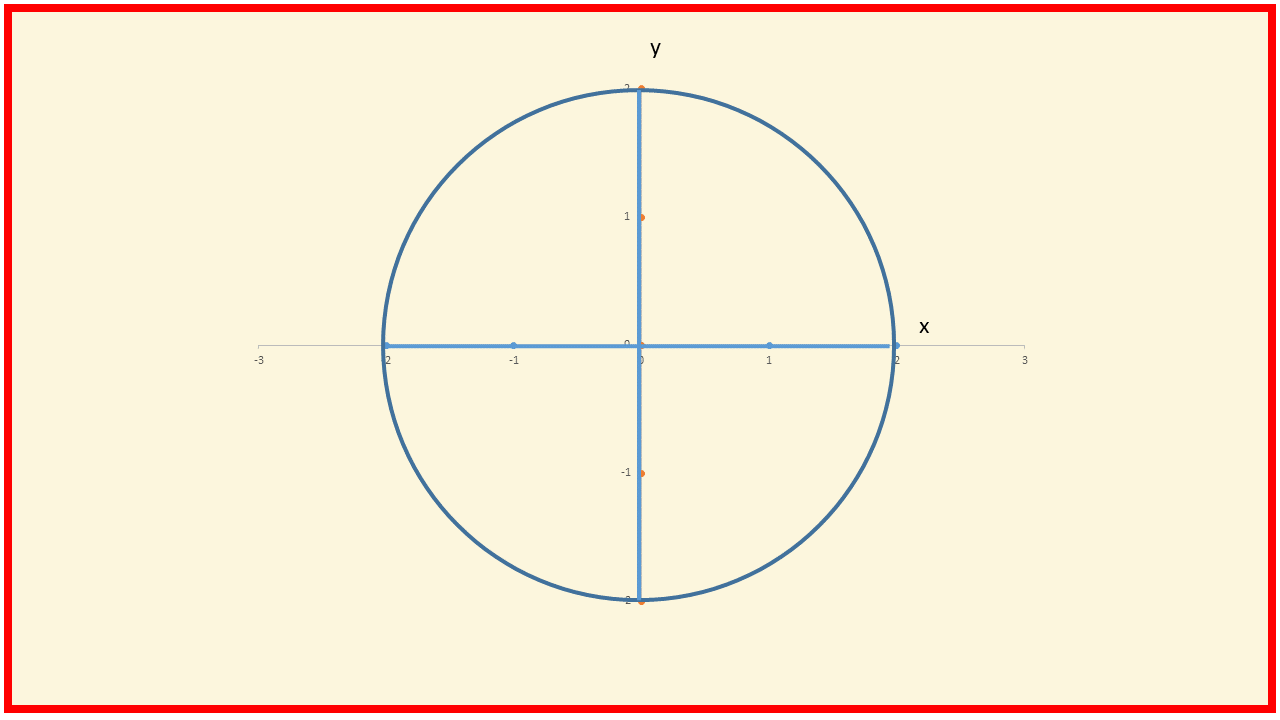

The simplest object in two dimensions is a disc, as shown below, with the two dimensions labelled x and y, though they could be labelled right-left and up-down if you prefer.

There is a fairly simple formula for this as well. You may be able to guess it from those given for the 1-D case.

Again r is the radius, a bit more obvious this time. And again r is 2, giving

This is the equation of the circular boundary of the disc. The 2-dimensional disc has a 1-dimensional boundary. This boundary, a circle, is also known as a 1-sphere (the line segment above can be termed a zero sphere – the boundary of the line segment consists of the two zero dimensional points). It is interesting to note that the disc has a centre, which is also the centre of the circle or 1-sphere. But the centre is not a point on the circle. Also, while the circle is the boundary or surface of the disc, the circle itself has no boundary or edge.

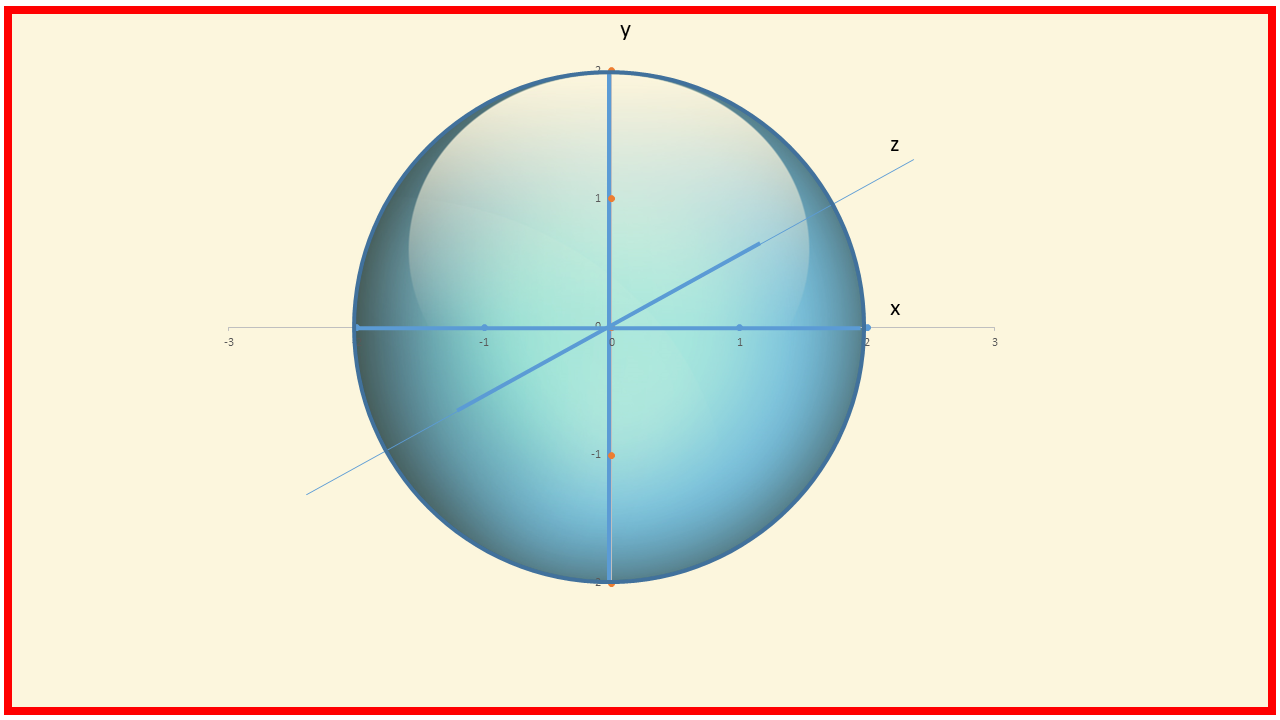

The simplest object in three dimensions is a ball or globe. This could be a snooker ball, a balloon or indeed the earth (if you ignore the fine detail).

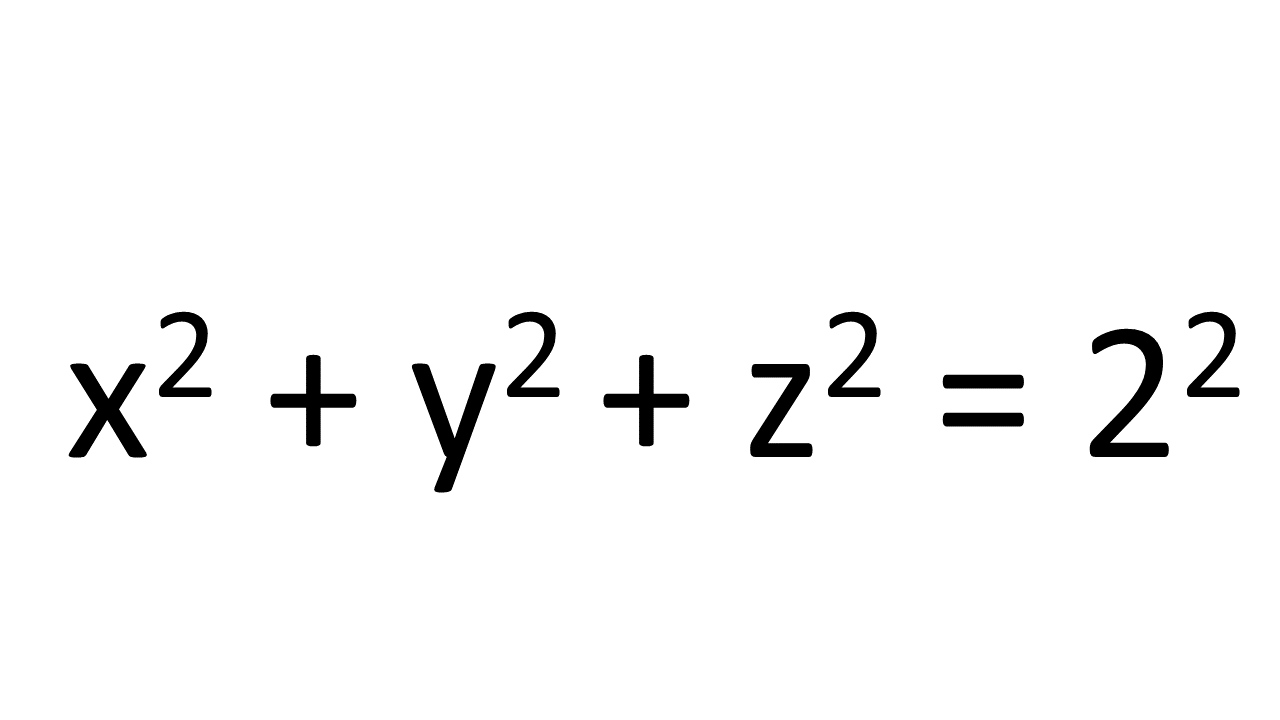

This time the third dimension is labelled z, though it could be called in-out if you preferred. The equation for a three dimensional ball, with a radius of 2, is (you might guess);

Again, this is the equation for the surface, or boundary of a 3-dimensional ball. This surface is 2-dimensional and is known as a sphere. In common language, a 3-dimensional ball is often called a sphere but strictly this is incorrect, but we can avoid any confusion by calling this surface by its correct name, a 2-sphere. The surface of the earth, which we inhabit, is a 2-sphere, give or take some fine detail. A 3-dimensional ball, such as the earth, has a centre. Its 2-dimensional surface, a 2-sphere, has the same centre but that centre does not exist on the 2-sphere. A 2-sphere, just like a 1-sphere, a circle, has no boundary or edge. There is no end of the earth. And every point in a 2-sphere is exactly the same distance from the centre. Every point on a simple 2-sphere is identical. (This is not quite true for the earth, even if the small scale geography is ignored, because the earth has an axis of rotation, which combines with the presence of the sun to make some points polar and others tropical.)

Some people have argued with me that a 2-sphere such as the surface of the earth is really 3-dimensional. If it makes them feel any better, a 2-sphere can be considered as a 2-dimensional surface embedded in 3-dimensional space. But it is 2-dimensional. This is because it only requires two numbers, such as longitude and latitude, to define any point on a 2-sphere such as the surface of the earth or a balloon.

We could stop here, but Einstein says our universe consists of spacetime, three dimensions of space and one of time. And our universe does not seem to be a simple three dimensional ball. It does not appear to have an edge nor does it appear to contain a centre. So let us carry on.

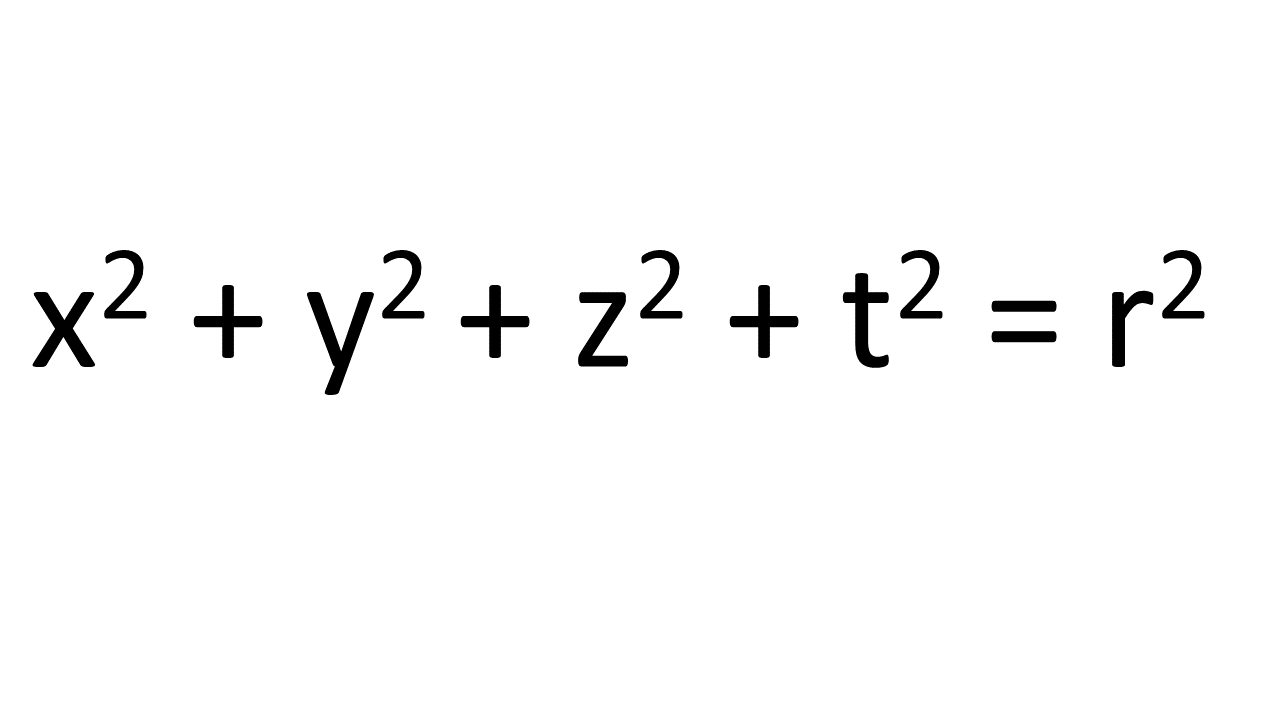

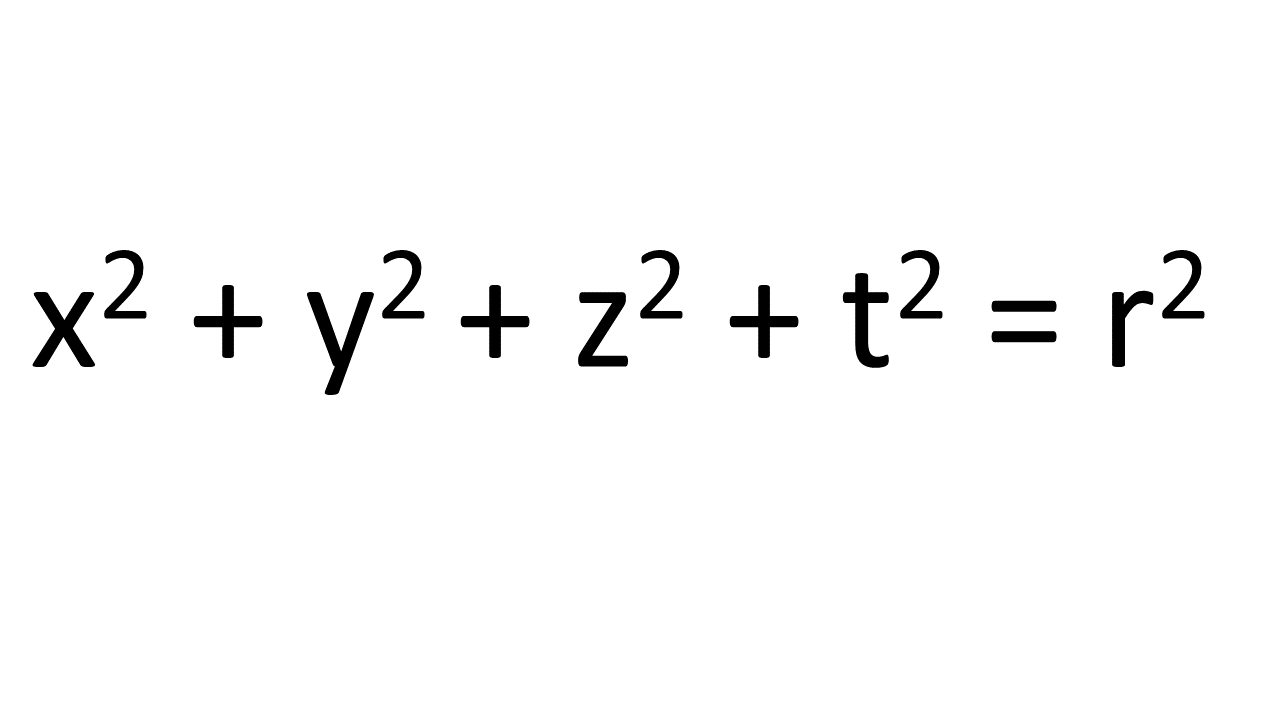

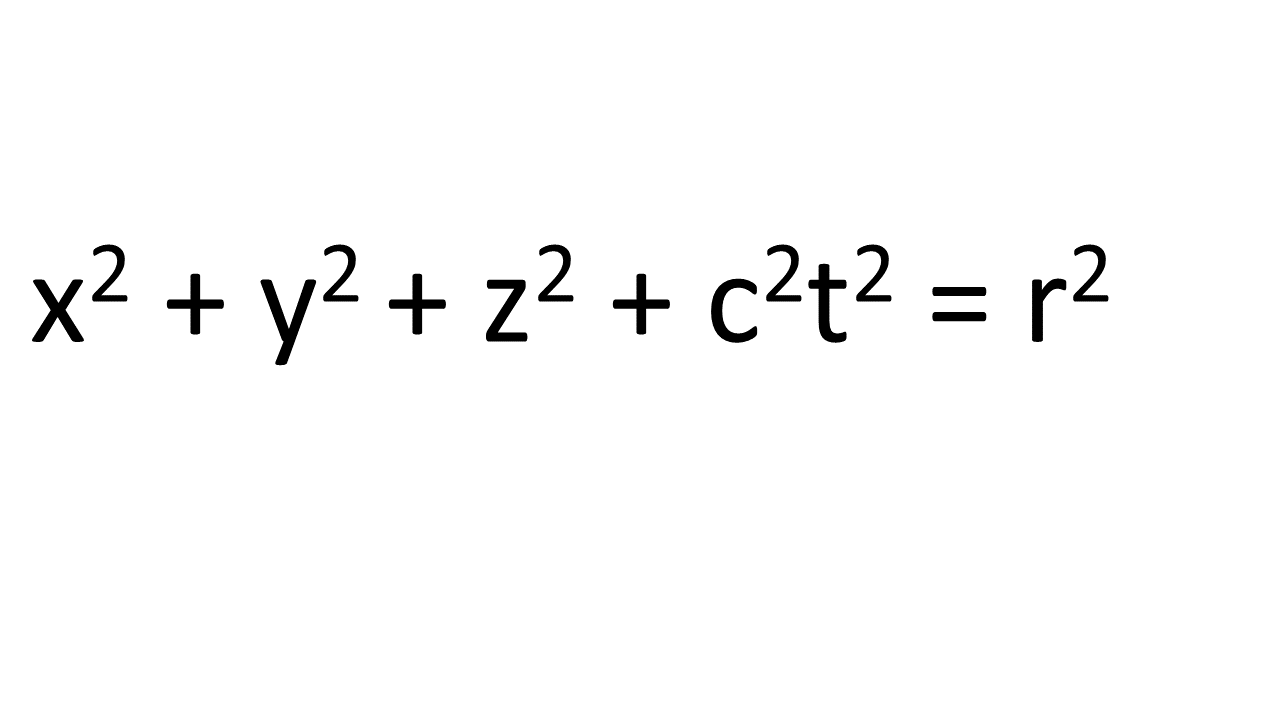

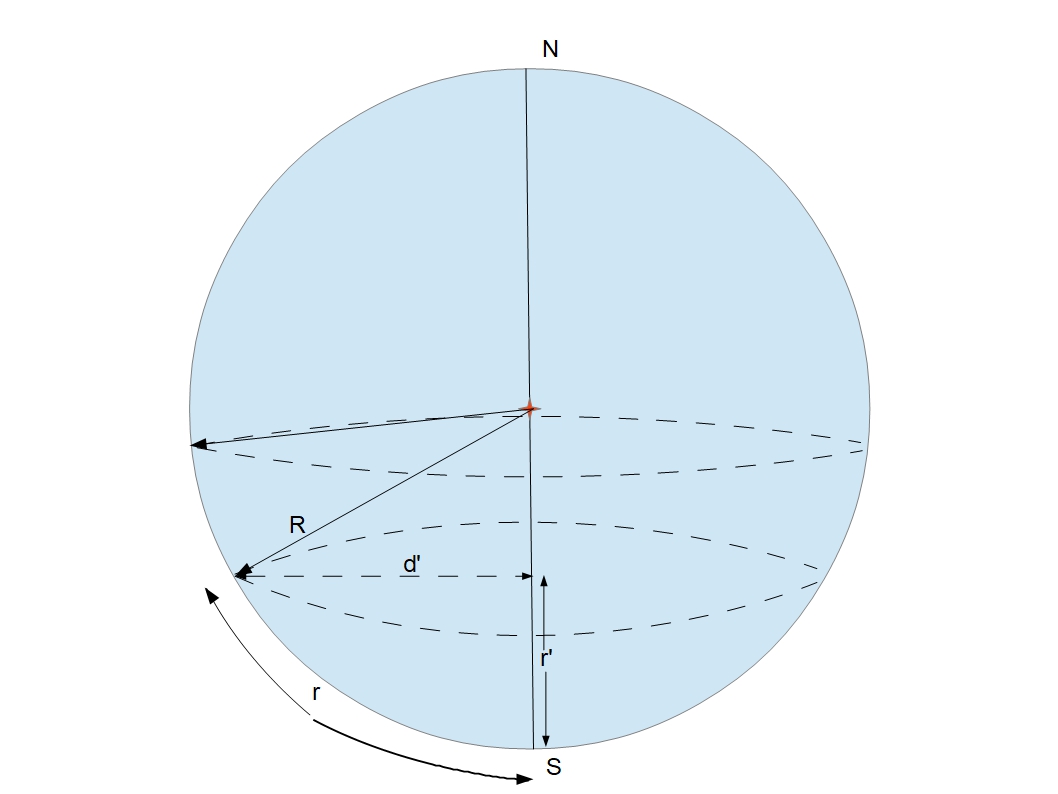

The simplest object in four dimensions is a 4-dimensional ball. A 4-dimensional ball has the following formula, simply by extrapolating from all of the earlier formulas.

I suppose it is obvious why I have called the fourth dimension ‘t’ but simply to understand what a 3-sphere is, you could call it anything you like. Just as the previous equation was not the equation for a 3-dimensional ball, but for its surface, a 2-sphere, this equation is not that of a 4-dimensional ball but it is the equation of its 3-dimensional surface, a 3-sphere. A 3-sphere is a finite 3-dimensional space, with a radius of r, but, just like the surface of the earth, it has no boundary or edge. And, again, just like the surface of the earth, it does have a centre, but that centre does not exist in the 3-sphere itself (it exists inside the 4-dimensional ball for which the 3-sphere is the surface). Just as every point on the surface of the earth, or a snooker ball if you prefer, is the same distance from its centre, so every point in a 3-sphere is exactly the same distance from its centre. I think a 3-sphere is an extremely attractive candidate for what our universe might be. Our universe started out expanding from a point, so it seems at first it could be a ball. But a little thought suggests it can’t be a simple 3-dimensional ball, because then it would have an edge and a centre. Einstein tells us the universe consists of spacetime, that is four dimensions (three of space and one of time). But our universe can’t be a 4-dimensional ball because:

I suppose it is obvious why I have called the fourth dimension ‘t’ but simply to understand what a 3-sphere is, you could call it anything you like. Just as the previous equation was not the equation for a 3-dimensional ball, but for its surface, a 2-sphere, this equation is not that of a 4-dimensional ball but it is the equation of its 3-dimensional surface, a 3-sphere. A 3-sphere is a finite 3-dimensional space, with a radius of r, but, just like the surface of the earth, it has no boundary or edge. And, again, just like the surface of the earth, it does have a centre, but that centre does not exist in the 3-sphere itself (it exists inside the 4-dimensional ball for which the 3-sphere is the surface). Just as every point on the surface of the earth, or a snooker ball if you prefer, is the same distance from its centre, so every point in a 3-sphere is exactly the same distance from its centre. I think a 3-sphere is an extremely attractive candidate for what our universe might be. Our universe started out expanding from a point, so it seems at first it could be a ball. But a little thought suggests it can’t be a simple 3-dimensional ball, because then it would have an edge and a centre. Einstein tells us the universe consists of spacetime, that is four dimensions (three of space and one of time). But our universe can’t be a 4-dimensional ball because:

- It would still have a centre and an edge

- We don’t live in four dimensions.

It seems to me just about the only thing left for our universe to be is a 3-sphere. Our universe is the 3-dimensional surface of a 4-dimensional ball.

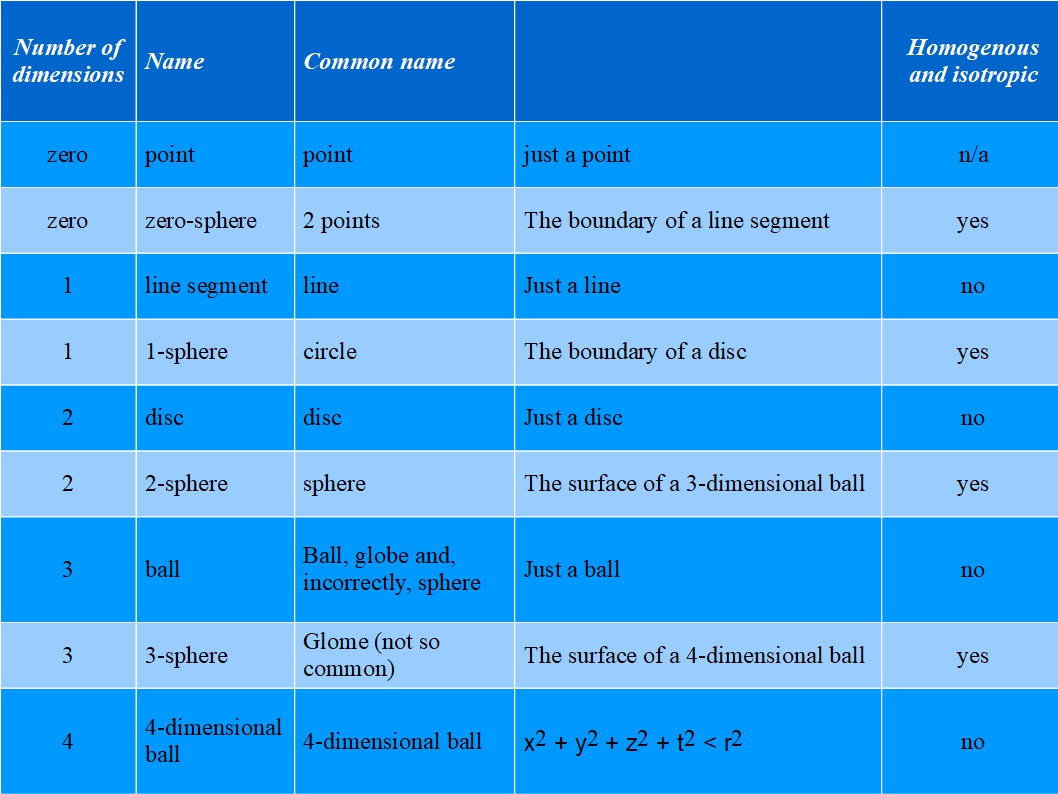

Before moving on, it might be useful to review where we have come so far, by way of the following Table, which lists the simple objects that can exist in up to four dimensions.

There is one shape missing, the 4-sphere, but that would be the surface of a 5-dimensional ball and I don’t wish to discuss five dimensions (four are enough for anyone!). There are only two 3-dimensional shapes, the ball, such as a snooker ball or the earth, with which we are all familiar and the 3-sphere (of course there are many more complicated shapes). It does not appear as if our universe can be a simple ball, since it would not be homogenous or isotropic, but it could be a 3-sphere. A 3-sphere is the only homogenous and isotropic 3-dimensional shape of finite size. I believe if our universe is not a 3-sphere then it must be infinitely large. If our universe is a 3-sphere, all of the questions asked in the first paragraph are answered, as well as many more, as you can see by continuing to read further.

According to Professor Carlo Rovelli, Einstein thought the universe might be a 3-sphere, though he does not say whether Einstein continued to have this view. As far as I can tell, a 3-sphere is the only homogenous and isotropic 3-dimensional shape, which fact alone, to my mind makes it an extremely strong candidate for the shape of the universe. (A homogenous shape is one in which all points are identical such as a circle or the surface of a snooker ball. A three dimensional ball is not homogenous since a point at the centre is not the same as a point at the edge. Isotropic is very similar to homogenous but actually means ‘looks the same in any direction’). All scientists agree that our universe must be homogenous.

More on dimensions.

So far so good. I am suggesting the universe we live in could be a 3-sphere. But a 3-sphere can only exist if a 4-dimensional ball also exists. So I am also suggesting the 4-dimensional ball consists of spacetime, three dimensions of space and one of time. But this then leads to a problem. If in the equation for a 3-sphere

t stands for time, then in this equation we seem to be adding length to time, which mathematically is not allowed. You cannot add apples and oranges you may have heard at school (you could if you renamed them both ‘pieces of fruit’ but forget that). Since we have three dimensions of space to one of time it is easier if we can do something to time, to convert it into length. This is possible if we multiply time by a constant with units of length/time.

T x L/T = L

L could be metres and T could be seconds so the constant would have units of metres per second. In other words the constant is a speed. And you can bet your bottom dollar that if this is correct, the constant is going to be the speed of light, c. I quite honestly had this idea from scratch but it turns out it is commonplace in the fields of relativity and cosmology to do this. So the equation for a 3-sphere existing in spacetime is now

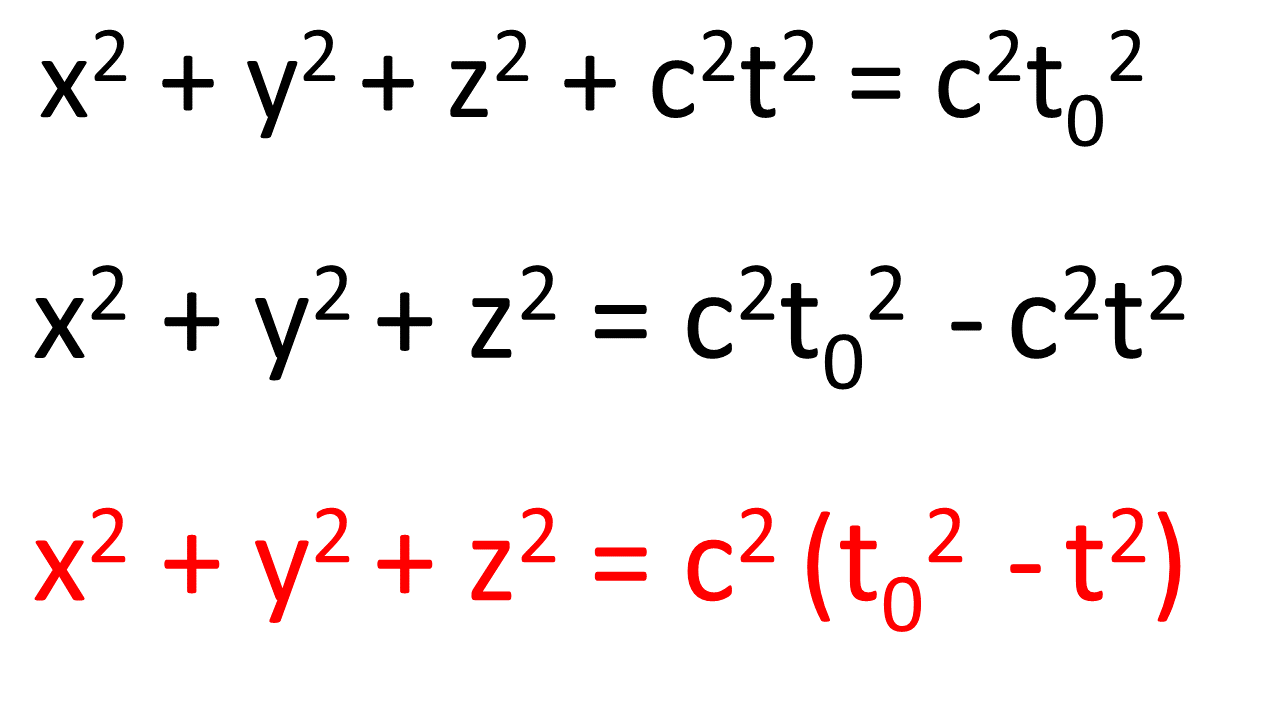

noting that (ct)2 = c2 t2 . If x, y and z are in metres and t is in seconds, then c, the speed of light must be in m/s. x (y and z) and t can be in any units you like (such as kilometres and years) but c must be in the corresponding same units (such as kilometres per year). But now we can convert r, the radius of the universe, into ct0 where t0 is a constant with units of time. t0 is the age of the universe. This changes the equation, which can be rearranged with a few simple steps, as below.

noting that (ct)2 = c2 t2 . If x, y and z are in metres and t is in seconds, then c, the speed of light must be in m/s. x (y and z) and t can be in any units you like (such as kilometres and years) but c must be in the corresponding same units (such as kilometres per year). But now we can convert r, the radius of the universe, into ct0 where t0 is a constant with units of time. t0 is the age of the universe. This changes the equation, which can be rearranged with a few simple steps, as below.

This final equation is my proposed equation for the shape of the universe. If you prefer you could call it a model of the universe. It is a 3-sphere expanding at the speed of light. x, y and z are the three familiar dimensions of space and t is time; t0 is the age of the universe; c is the speed of light and c t0 is the radius of the universe. It describes a 3-dimensional space with a finite radius. Just like a circle or the surface of the earth, it has a centre, but that centre does not exist within the space itself (the centre is inside a 4-dimensional ball of which this 3-sphere is the surface). Every point in our 3-sphere universe is exactly the same distance, r, from its centre. And again, just like a circle or the surface of the earth, this space has no boundary or edge. All of the questions at the top of this blog have been answered but I did promise that several more would also be answered, including ideas about the very beginning of the universe, so read on if you like.

The strange coincidence of the Hubble constant.

In the 1920s, the American astronomer, Edwin Hubble, discovered that most objects in the universe, and all distant objects, were receding from us. Furthermore he discovered that the more distant they were, the faster they were receding. Together with others, he found that if you plotted the speed at which an object, such as a galaxy, is receding from us, against its distance you get a straight line.

v = H x d

The velocity, v, equals the distance, d, times a constant, known as the Hubble constant, H, in his honour. For our purposes it is important to appreciate the units of H. This can be done by re-arranging the equation

H = v/d

The units of velocity are length/time (L/T) eg metres/second, while the units of distance are of course length (L) such as metres. So the units of H are (L/T)/(L) which is 1/T. The units of the Hubble constant are reciprocal time, eg per second. Now here is the strange coincidence. The measured value of the Hubble constant is usually quoted as in the region of 72 km/sec per megaparsec. Now megaparsec is simply a very large distance which is useful when considering astronomical separations. But for our purposes we need both distances to be in the same units, so let us use the more familiar kilometre. 1 megaparsec equals 3.1 x 1019 kilometres. So the Hubble constant is therefore 72 / 3.1 x 1019 per second which is 2.3 x 10-18 per second. Now here is the strange coincidence. The reciprocal of the Hubble constant is 4.3 x 1017 seconds and this just happens to be the age of the universe, generally accepted to be 13.8 billion years. (Actually I have just checked and it comes out to be 13.7 billion years, but as you might expect there is a little bit of uncertainty as to the exact value of these numbers)

Scientists do not like coincidences. They generally indicate a lack of understanding but the scientific community is currently making no attempt to explain this one. They seem quite happy to accept it as a coincidence. But what does the model proposed in this blog say. If the 3-sphere has been expanding at the speed of light for 13.8 billion years, its radius will be 13.8 billion lightyears. So two points, separated by 13.8 billion lightyears are separating at the speed of light which gives a Hubble constant of 300,000 km/s / 13.8 billion lightyears (the speed of light is 300,000 km/s) . I have just checked this (it only took a few seconds using a spreadsheet, you could easily do it with a little practice) and it comes out to be 2.3 x 10-18 per second. Our proposed model calculates the Hubble constant perfectly and there is no coincidence.

Some of you might think you have spotted a sleight if hand here. The radius of a 3-sphere is not after all part of the 3-sphere, so why would a Hubble constant calculated this way apply to the 3-sphere itself. Well, if you take a circle with a radius of r and place two points on the circle separated by the same distance, r, then if the radius of the circle were to double, so would the separation of the two points. If the radius is growing at a certain speed the separation of the two points will grow at the same speed. This is also true for a 2-sphere such as the earth and is also true for a 3-sphere. There is no sleight of hand. The calculation based on the radius will apply to any two points in the 3-sphere separated by the same distance, r.

And just a little more maths. In the 3-sphere model, the radius of the universe equals its age times the speed of light.

radius = c x age, or

c = radius/age

and as just explained above, the velocity of separation, c equals H times the distance of separation, when that is equal to the radius of the universe

c = H x radius

Since both the right hand sides equal c, then they equal each other.

H x radius = radius/age

Divide both sides by the radius and we have

H = 1/age.

In the 3-sphere model, H, the Hubble constant, is the reciprocal of the age of the universe, exactly as measured by astronomers. There is no coincidence.

Relativity

What! you are still here. Actually I don’t think this section is going to be hard at all. It will simply make a connection between a statement made by professor Brian Cox on relativity, and the 3-sphere model.

There are two theories of relativity. Einstein’s special theory of relativity is the one that states that the speed of light is a universal constant for every observer and as a consequence moving objects get heavier and time slows down as speed increases and of course contains the famous equation

E = M c²

Einstein’s general theory of relativity states there is no difference between gravity and acceleration and that gravity is in fact the curvature of space (space being curved by mass). But it is this theory which leads to the prediction of black holes and is often used to prepare models of the universe. Mass causes space to curve. The maths associated with this theory is fiendishly difficult and thankfully (for me) we will stick to the special theory.

The statement made by Brian Cox is this. A very useful way of viewing the special theory of relativity is to consider that everything in the universe is moving through spacetime at exactly the speed of light. If any object is moving through space at the speed of light it must be stationary in time and if an object is stationary in space it must be moving through time at the speed of light. (I think the speed of light through time must be 1 second per second, which of course is just 1, but Brian Cox did not say this). You can then use Pythagoras’ theorem to relate the speed through space to the speed through time (v² + t² = c².) Brian Cox does not go on to say why every object in the universe is travelling at exactly the speed of light but of course that is precisely what is predicted by our expanding 3-sphere model. Every point in a 3-sphere is the same distance, r, from the centre. So if r is expanding at the speed of light, then everything in the 3-sphere is also moving at the speed of light. The 3-sphere model certainly agrees very well with this way of looking at special relativity.

Those with a little physics might remember that the kinetic energy (ke) of a moving object equals one half times its mass times its velocity squared. So for an object moving at the speed of light, which all objects are, even if they appear stationary to us,

ke = ½ M c²

This is not so different from Einstein’s famous equation.

Interlude (you can ignore this if you like)

I am trying not to put too many equations into this blog but I think it is really neat to say a bit more about my comment on Pythagoras’ theorem. Firstly, in spacetime, all dimensions in space (x, y and z) are at right angles to each other, that is what is meant by the word dimension, and the same is true for the time dimension. Time is at right angles to each of the space dimensions. That is why we can use Pythagoras theorem when we relate speed to time. So if we start with

v² + t² = c²

we can rearrange this to be

t² = c² – v²

or

t = √(c² – v²)

and also, if v=0, t0 , the speed of time for an object at rest, is

t0 = √(c²)

which of course is just c, as Brian Cox said, and so t/t0 the ratio of time for a moving object to time for an object at rest, is

t/t0 = √(c² – v²)/√(c²)

and if we divide both the numerator and the denominator on the right hand side by √(c²) we get

t/t0 = √(1 – v²/c²)

which is the familiar (to some) equation for time dilation in relativity. Actually as time slows down, that is gets smaller, intervals get longer, so if t and t0 are replaced by delta t and delta t0, the reciprocal applies and we have

Δt0/Δt = √(1 – v²/c²)

Also note that I said I thought the speed of light through time was 1 second per second (for a stationary object), but I wasn’t certain. But if we are only calculating the ratio t/t0 , or delta t0 / delta t, the units do not matter.

More detail on an expanding 3-sphere

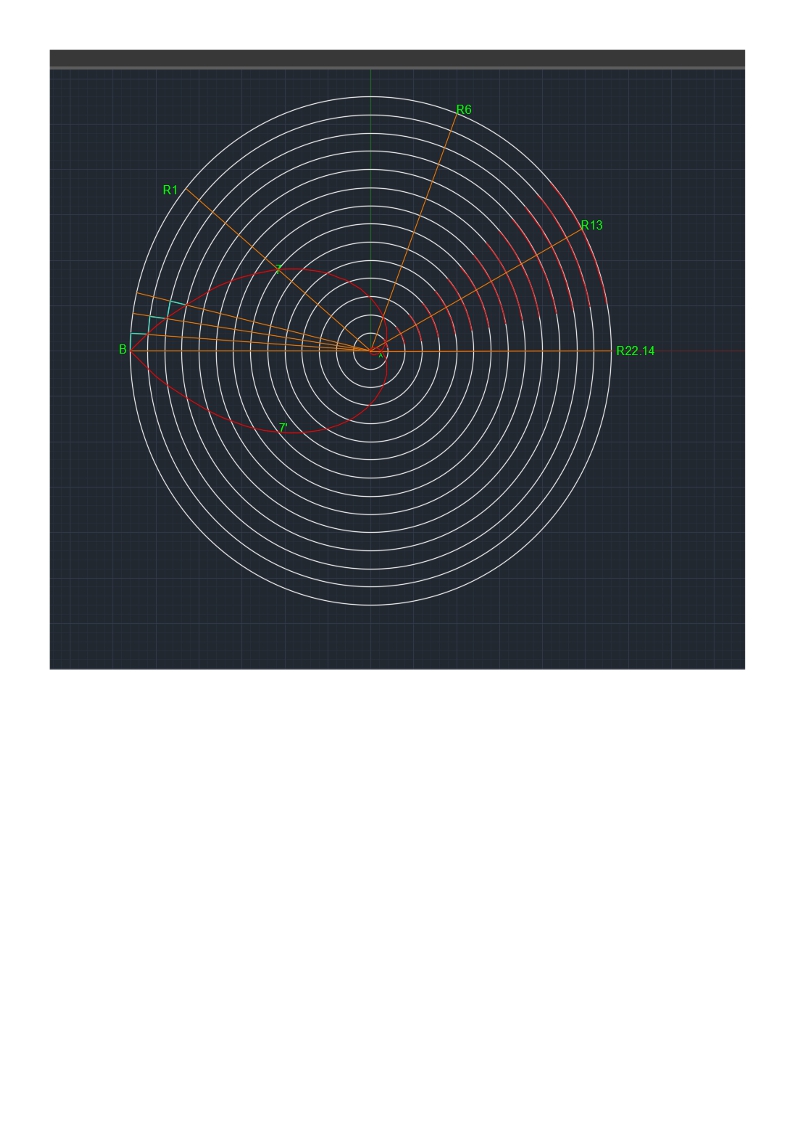

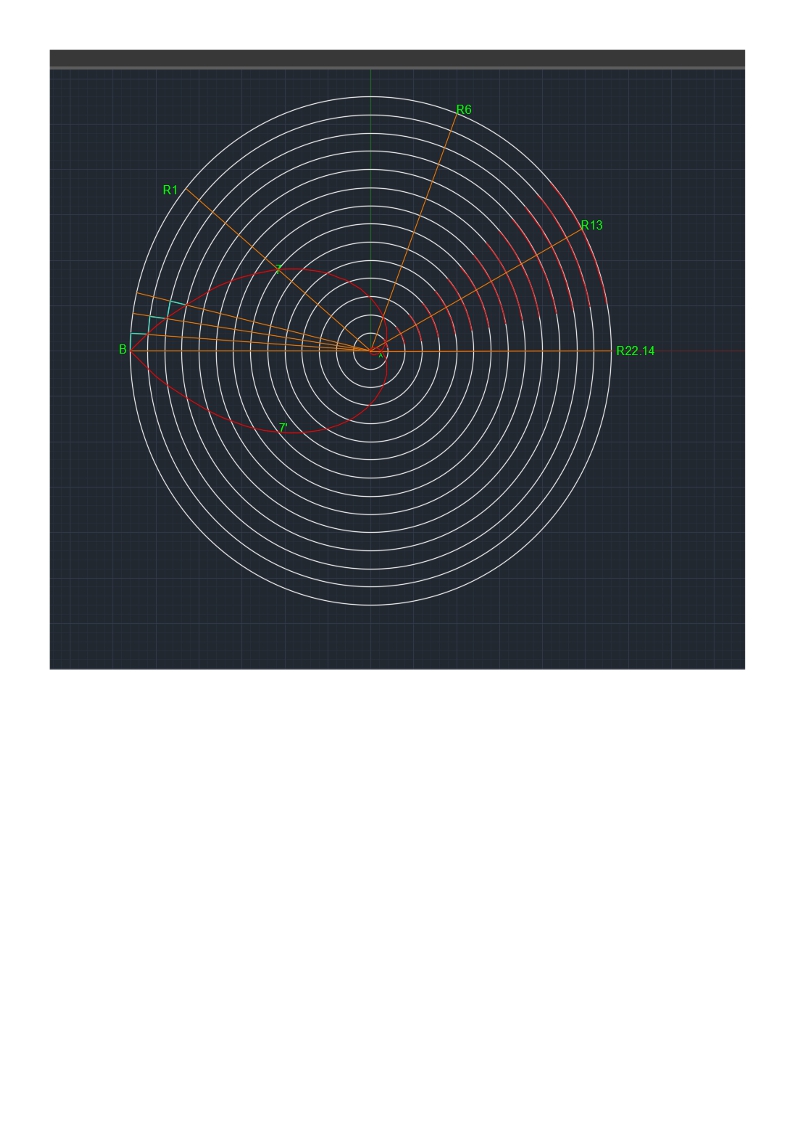

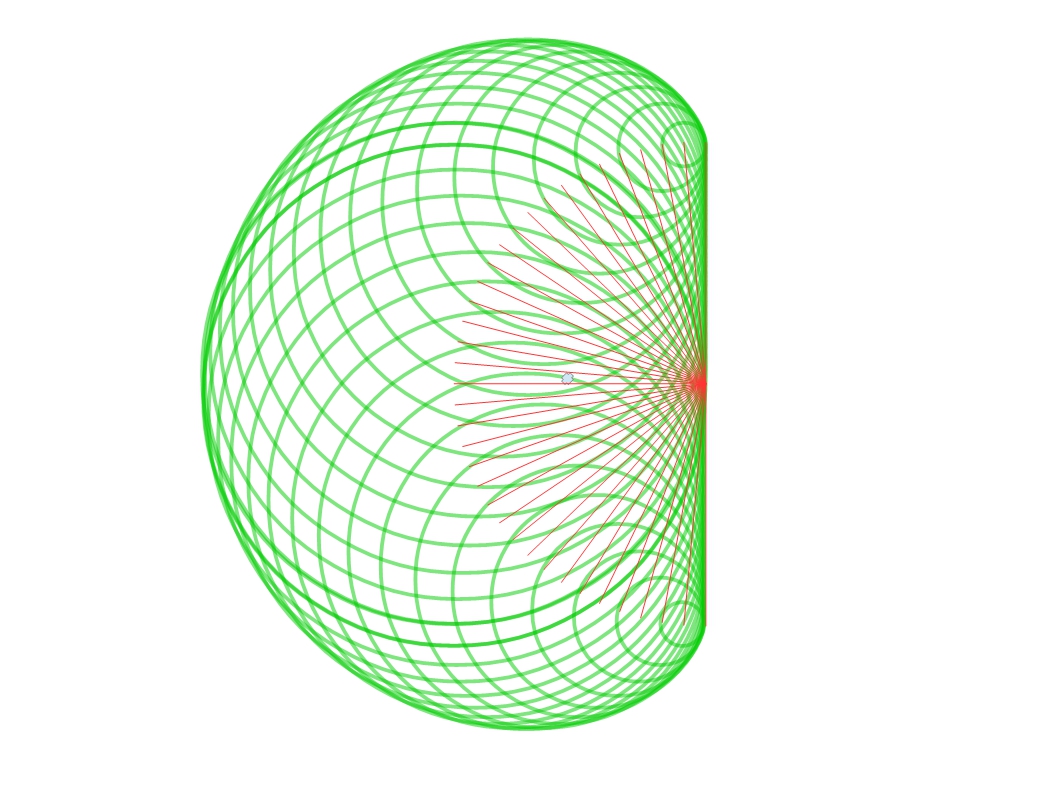

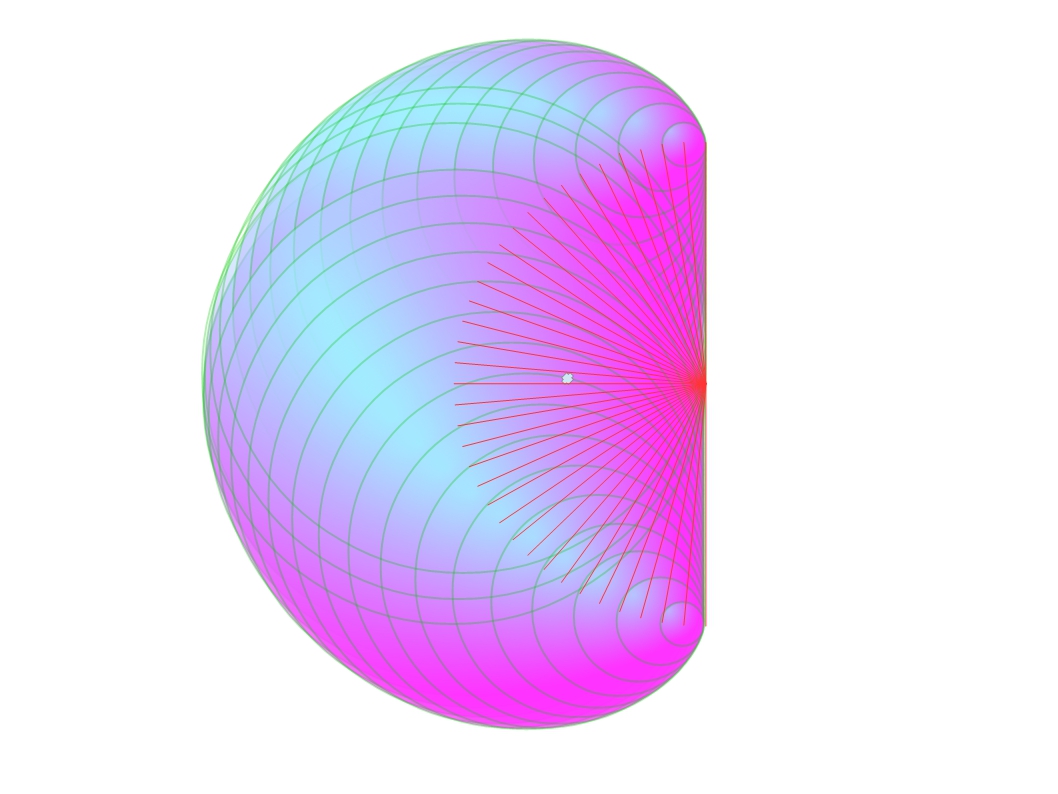

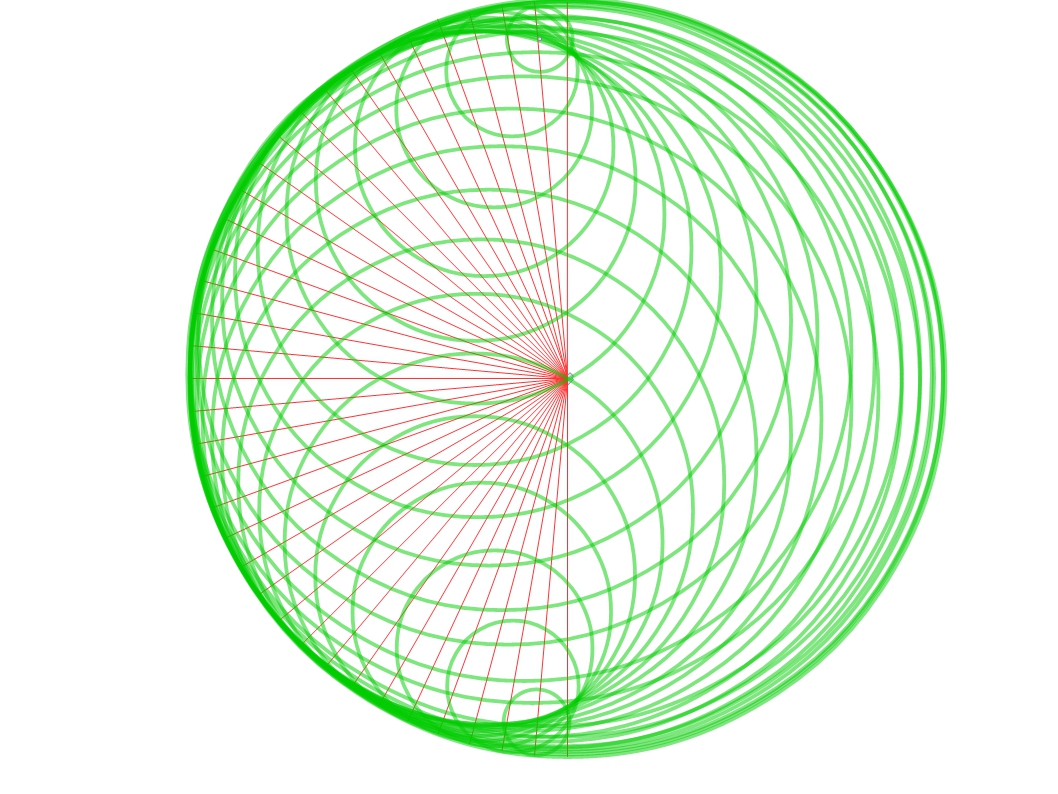

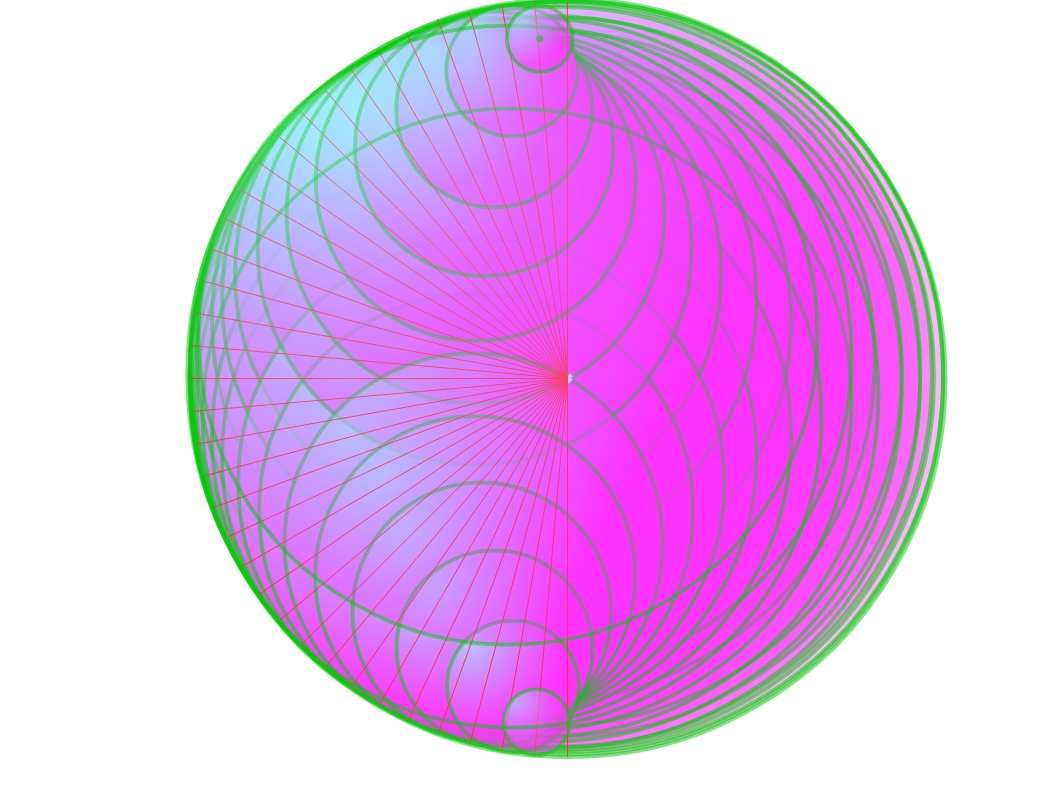

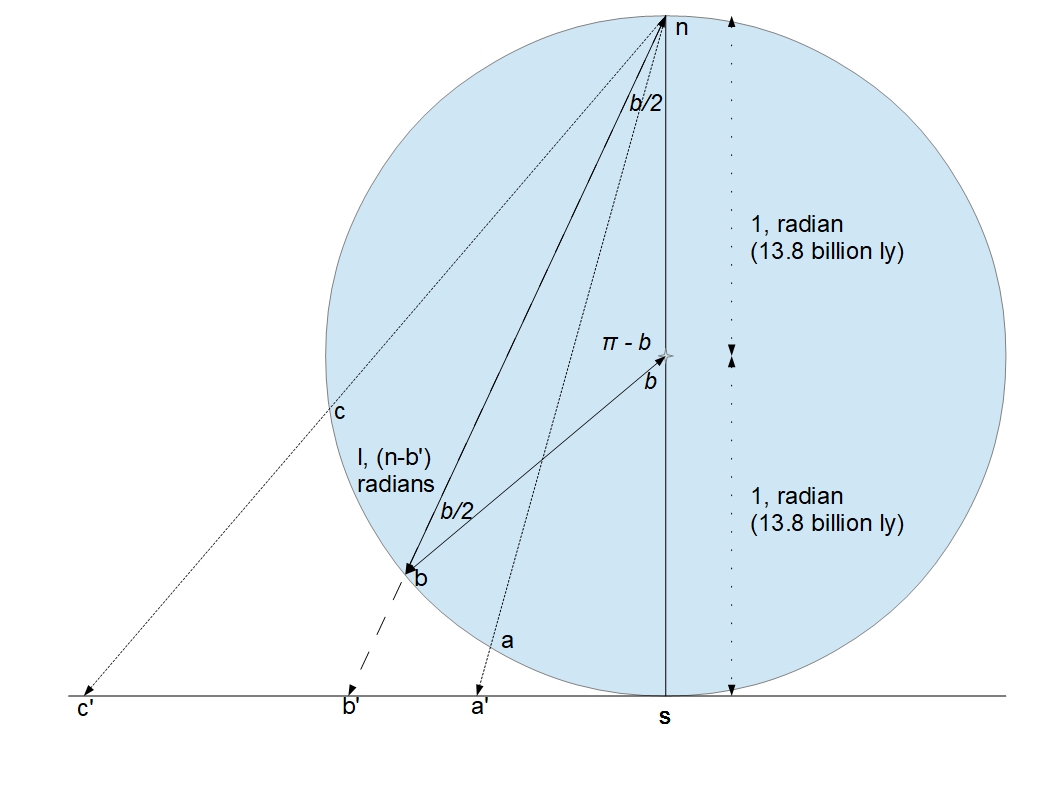

I hope this doesn’t sound daunting. Actually I think it is my favourite bit, and its mostly visual. The picture below shows our universe expanding for 14 billion years, with a snapshot every billion years. B is an observer in our present day universe. It is worth spending a little time thinking about what this picture represents. Superficially it is fourteen circles in two dimensions. I would prefer you to think of it as fourteen discs (black or transparent on a black background) each with a white surface or boundary. Each disc is 2-dimensional and each boundary is a circle or 1-sphere. B, an observer, can only move in 1 dimension, such as forwards or backwards. If I now say consider this picture to be a set of cross sections through an expanding ball, I suspect most will not have too much difficulty with this. In this case, each white circle is now a cross section across the spherical surface, a 2-sphere, of each 3-dimensional ball. The observer B now resides in a 2-dimensional universe where he can move forwards and backwards or left and right. All I am asking now is that you view this picture as a cross section through a 4-dimensional ball. Each white circle is now a cross section through the 3-dimensional surface of a 4-dimensional ball, a 3-sphere. The observer, b, now exists in three dimensions, forwards and backwards, left and right or up and down. Any movement he makes, in any direction, would, in this picture, only appear as motion around the outer circle.

.

It is tempting to say that the direction from B to the centre is the time direction and that movement in this direction is not possible without leaving our 3-dimensional universe. There is a difficulty here, since if B moves a quarter of the way around the universe, the radius now appears to be one of the space dimensions. This difficulty goes away if we switch to polar co-ordinates where can now say that the radial co-ordinate is always the time co-ordinate, but I don’t really like polar co-ordinates so have not taken this further.

Now I wish to consider what happens to a ray of light, or a photon if you prefer, in this expanding 3-sphere universe. Let us consider a ray of light arriving at the observer, B. It turns out to be rather difficult to calculate its path, because we do not know where it started from, but the calculation is much easier if we consider a ray of light leaving the observer, going backwards in time. Now it is a feature of light that light paths are always reversible. That is if light travels from a to b, then light travelling from b to a always follows the same path in reverse. So let us start with light travelling through the universe for 1 billion light years. This is shown by the turquoise path around the outer circle. During this time the universe will have shrunk by 1 billion light years. This is shown by the turquoise path now heading towards the centre. The overall path of the light over this billion years, is shown in red. This is shown repeated for two more steps. When I started doing this I felt certain the light ray would spiral into the centre, the point of the big bang, but reality turned out to be much more surprising. When I repeated this for a total of fourteen steps, the light ray did not reach the centre but things became rather messy such that I lost confidence in what I was doing. I then realised that every time I made a new step, the light ray made an angle of 45 degrees to the circle it was just leaving. There is a name for the curve that is being produced. It is an equiangular spiral or even better known as the logarithmic spiral. It is rather famous. It is the shape of the nautilus sea shell. It is the shape produced by the Fibonacci series, generated by the consideration of breeding rabbits. It also leads to the golden ratio, the ratio of the sides of our A3, A4 etc sheets of paper and is also much used in architecture. And if that was not enough it leads to the spiral patterns of seed heads such as those of the sunflower.

The logarithmic spiral has a formula to describe it. For information it is, in polar co-ordinates using r, the radius and ϴ, the angle.

r = a exp(ϴ cot b)

b is the constant angle that the spiral makes with the circles, which in our 3-sphere universe is 45 degrees. ‘cot’ equals cotangent which is the reciprocal of the tangent. The tangent of 45 degrees is 1 and the reciprocal of 1 is 1, so the formula simplifies to

r = a exp(ϴ)

exp stands for ‘e to the power of’. e the base of natural logarithms has a value of 2.72. mathematicians like to use ‘e’ when appropriate but you could replace it by ’10 to the power of’.

This formula can now be used to calculate the path of a ray of light as it reaches the observer B in the picture. It is shown by the red curve. When the light path moves through 180 degrees, it reaches the point A, which is not the centre of the universe (at the moment of the big bang, as I originally thought it might be) but is in fact a point in the universe when its radius was 0.6 billion years and also when it was 0.6 billion years old. The beam of light does not stop here. The picture shows the ray continuing for a further 180 degrees where it now appears very close to the centre. The ray is now coming from the universe when it its radius was just 26 million years and it was just 26 million years old. The ray continues to circle the centre of the universe getting ever closer, but it never gets there.

It might appear to some that if the ray circles the centre of the universe for ever, it must have infinite length, but this is not true. Each circuit gets smaller and the sum is finite. All light rays have a finite length. This is just the same as summing the series 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + .. + .. If this is carried on for an infinite number of terms, the sum is exactly 2. On this basis it is a finite distance from the observer to the centre of the universe at the moment of the big bang. But looking at this from a different angle I will show that it can after all be considered to be an infinite distance from the observer to the point of the big bang.

If the observer at B were to look in the opposite direction, any light he sees would be following the lower red curve which also passes through the point A. Actually, no matter what direction they look in, after around 44 billion lightyears they will see the same point, A. This may seem strange at first but it is no different to what happens on the earth. Imagine a group of people at the south pole. If they all set off in different directions and follow straight lines, they will meet up at the north pole (if they all travel at the same speed). But an observer at B, or anywhere in our present day universe, can only see in our present day universe, which is the outer white circle. By the time a light ray travels from point A to the observer, at B, point A will have expanded, along with the universe, to the point labelled R22.14 (a reason for the odd label will be explained shortly).

If the observer at B looks through the present day universe to a galaxy at R1, they will see it as it was 7 billion years ago. If at a galaxy at R6, they will see it as it was 12 billion years ago, at a galaxy at R13, 13 billion years ago, and a galaxy at R22.14, as it was 13.4 billion years ago, when the universe was just 0.6 billion years old.

If an observer looks in any direction for 44 billion light years, they will see their own antipodal point. At this distance, which is further than any yet seen, the universe will look the same in any direction. It will probably look dark but if there just happened to be a galaxy at this point, perhaps it would look bright. At this point the observer has seen the entire universe. But there is nothing to stop an observer looking even further, when they are likely to see yet more galaxies. How can this be? Well the observer will start to see galaxies twice, but at two different ages. In fact if they look for 88 billion light years they will see themself (strictly their location) as they were when the universe was just 26 million years old. And on and on, though at some point soon after this the universe is thought to have turned opaque to light.

Red Shift

In the section above on the Hubble constant I did not say how Edwin Hubble knew that distant galaxies were receding from us. The answer is the red shift. If starlight, or any light, is passed through a prism or a diffraction grating, it is split. Light comes from any substance as it is heated and light from different elements has a distinctive spectrum when it is split. But at first sight the light from distant galaxies did not show any of the spectra characteristic of known elements. Closer inspection showed the characteristic spectra were present but only if the characteristic wavelengths had become longer (for visible light that means more red). This red shift is often explained in terms of the Doppler effect. The classic Doppler effect is observed when a whistling train passes by. As the train passes, the pitch of the whistle drops. As the train approaches, the wavelength of the sound of the whistle is compressed by the ratio of the speed of the train to the speed of sound. Shorter wavelength equals higher frequency equals higher pitch. As the train passes by and starts to recede the wavelength of the sound is stretched by the same ratio and the pitch reduces. You could replace the train by a police car with its siren on (just as long as the police car does not stop when it reaches you). The Doppler effect can explain the red shift of galaxies receding at velocities which are a significant fraction of the speed of light, but as the velocities become even more significant the Doppler formula needs to be corrected for relativity. Moving even further out into space, the apparent speed of recession, before too long, exceeds the speed of light (though in truth no object ever moves faster than light) and the Doppler formula is no longer useful. Fortunately there is a much simpler way to view cosmic red shift. This is that as the universe expands, the wavelength of existing light expands with it.

If in our picture light is emitted from the point labelled 7, when the universe was 7 billion years old, by the time it reaches our observer at B, the universe will have doubled in size. And to our observer, the point labelled 7 will appear to be at R1. Now a doubling of wavelength corresponds to a red shift of 1. So when our observer sees an object at R1 it will have a red shift of 1. In fact the formula for red shift is

red shift = observed wavelength/emitted wavelength -1

As the universe shrinks as we move backwards in time, it is given a scale factor. The formula for scale factor depends on the model chosen for the universe but it is extremely simple for our 3-sphere model. As we look through our present day universe the scale factor equals the age of the universe when light left the object ie galaxy, in view divided by the age of the universe now. And the red shift is as follows

red shift = 1/scale factor – 1

An interesting feature of the cosmic red shift, as it is commonly known, is that it does not depend at all on the velocity at which an object is receding (though it does of course require the object to be receding).

The picture illustrates the age of the universe corresponding to a selection of red shifts according to the 3-sphere model, as shown in the Table.

|

Age observed, billion years |

Angle made, radians |

Apparent distance, billions ly |

redshift |

comments |

|

7 |

0.7 |

9.8 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

1.9 |

26.6 |

6 |

|

|

1 |

2.6 |

36.4 |

13 |

|

|

0.6 |

pi |

44 |

22.1 |

First convergence, or antipodal, point |

|

0.026 |

2 pi |

88 |

535 |

Second convergence point, ‘self’ image. |

|

0 |

∞ |

∞ |

∞ |

The big bang |

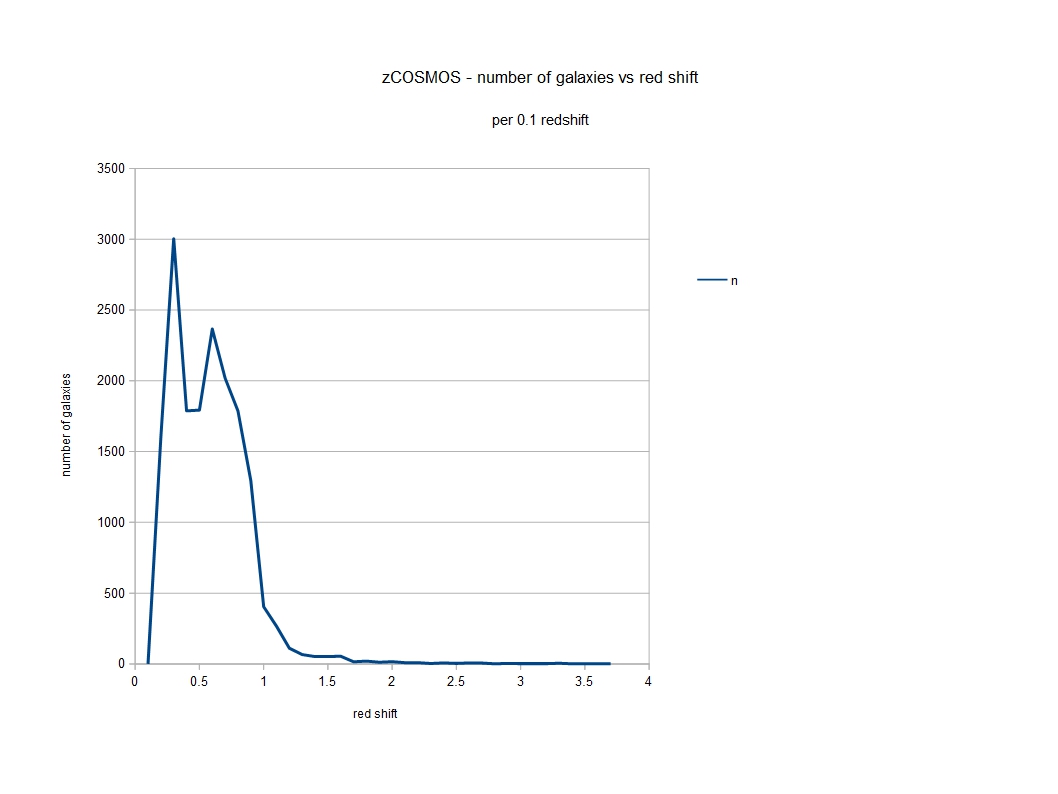

So far the greatest red shift observed is around 12. It will be a great test of the 3-sphere model if we are ever able to observe red shifts in the region of 22, when we may be able to determine whether such an antipodal point exists.

Up to around a red shift of 10, the age of the universe, for a given distance, predicted by the 3-sphere model is around the same as that predicted by scientists’ currently preferred model known as ‘lambda cold dark matter’ with added inflation (lambda stands for dark energy). Beyond a distance of around 30 billion light years, the standard model begins to predict greater red shifts and younger ages for the universe than the 3-sphere universe does. But since astronomers have only been able to confirm distances to objects at around 15 billion years, we are currently well short of being able to differentiate between the two models by observation. Though near the end of the blog a different method is presented which seems to strongly favour the 3-sphere model.

Inflation

For a number of reasons, most cosmologists believe the extremely young universe, starting from when it was around 10-35 metres in size, went through a period of extremely rapid expansion, which they have termed inflation. During this period, the universe must have been expanding very much faster than the speed of light. Inflation explains features of the universe such as its uniformity,

its density and its fine structure. Though most cosmologists believe inflation occurred, there is little agreement as to how or why it occurred. I believe the 3-sphere model explains inflation in a very simple way. If we look at our picture of the expanding universe, we see that going back in time, a photon would spiral indefinitely towards the origin, the point of the big bang, never actually getting

there. Every time it makes a circuit, the universe will shrink by a factor of 535 (that number is just the result of using the formula for a logarithmic spiral but you can see from the picture that it has already shrunk by a huge amount in just one circuit). It takes around 22 circuits for the universe to shrink from its present size to a radius of 10-35 metres, the Planck length which many believe

to be the smallest meaningful length. At this moment the universe is around 1060 times smaller than its present size. The scale factor is around 10-60 and so the red shift is around 1060 (we can safely ignore subtracting 1). If we could see back that far, a photon would seem to us to have been travelling at 1060 times the speed of light since by the time we see it the universe will have expanded from a radius of 10-35 metres to 14 billion light years, a factor of 1060. Any structure in such an early universe will have expanded by a factor of 1060 by the time it reaches the present day universe, which is just what inflation is required to explain. Inflation simply results from the way we observe the universe in the distant past. In fact nothing has ever been travelling faster than the speed of light. It might be said that inflation is a virtual phenomenon. And inflation has never stopped, it simply winds down as the universe approaches its current size. Read on a bit for an alternative diagram which I think explains inflation even better.

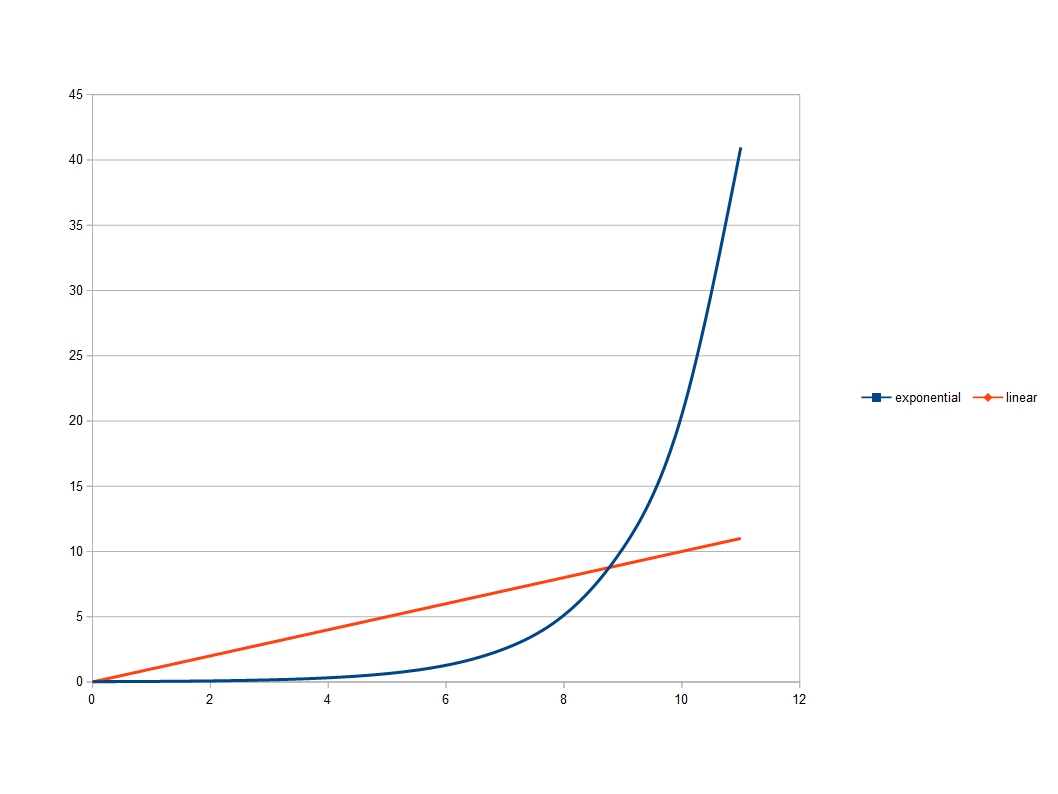

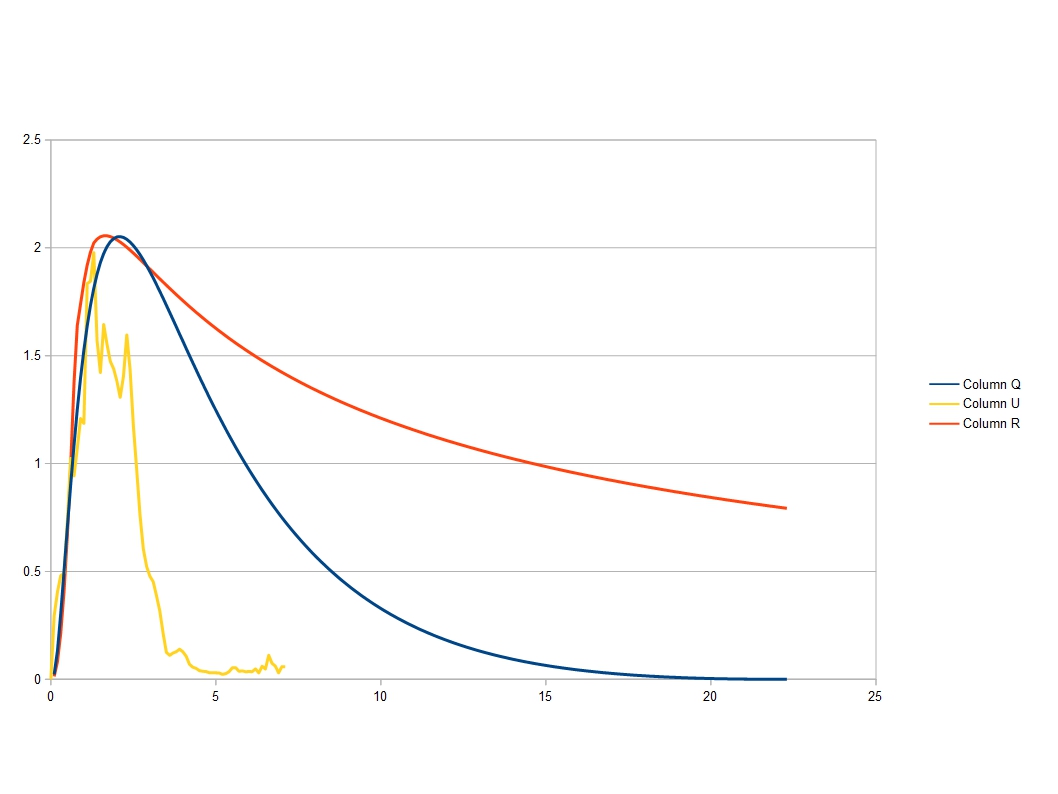

I must admit to a slight niggle when writing this. Most of the texts on inflation say that during inflation, the universe grew exponentially. I am not certain whether they mean strictly exponentially, with a constant doubling time, or just extremely quickly. But this appears to run counter to the 3-sphere model which is expanding linearly, at the speed of light. ‘Everybody’ knows that exponential growth is much more rapid than linear growth. But ‘everybody’ is wrong. Linear growth is faster than exponential growth, as I realised while contemplating a tray of courgette seedlings. At least it can be, and always is if you go back far enough towards the start of the growth. As you can see below.

At the start of growth, linear growth is more rapid than exponential growth. You may think I have cheated by my choice of constants for the curves, but no matter what constants you choose, if you go back far enough in time, linear growth always outstrips exponential growth.

It no longer worries me that the 3-sphere model never predicts exponential growth. Linear growth can be more rapid still.

Weighing the universe

It might seem strange that the 3-sphere universe has a weight (more strictly a mass) which can be calculated very easily. This can be done by considering that when light travels through the 3-sphere universe, it is always the same distance, 14 billion light years from its centre. It could be thought that light is in orbit around the universe in which case the speed of light is the escape velocity of the universe. But there is a very simple formula for the escape velocity of a body in orbit, as shown below

Ev = √(2 G M/r)

Ev, escape velocity, in the 3-sphere model, C, 3 x 108 m/s

G, universal gravitational constant, 6.67 x 10-11 m³ kg-1 s-2

M, mass, unknown

r, radius, 14 billion ly

(Actually this is the formula for the event horizon of a black hole, known as the Schwarzschild radius. Newtons formula for the conditions for an orbit misses out the factor of 2. In the case of the 3-sphere universe, the velocity is the speed of light and the Schwarzschild equation seems more appropriate. But if we were to use Newtons equation, no conclusions would significantly change.)

This equation can be rearranged to give

M = C² r / 2G

The resulting value for M is 8.9 x 1052 kg. This is an extremely respectable estimate for the mass of the universe. (This calculation is identical to that which results from considering the 3-sphere to be a black hole). I have just Googled ‘mass of the universe’. The first response estimates that the mass of visible matter in the visible universe is 6 x 1051 kg but since visible matter only makes up around 4% of the total mass, the rest being dark matter and dark energy (energy has mass as well, E=MC2) the total mass of the visible universe is estimated to be a little over 1053 kg. I think this is amazing agreement with the 3-sphere model.

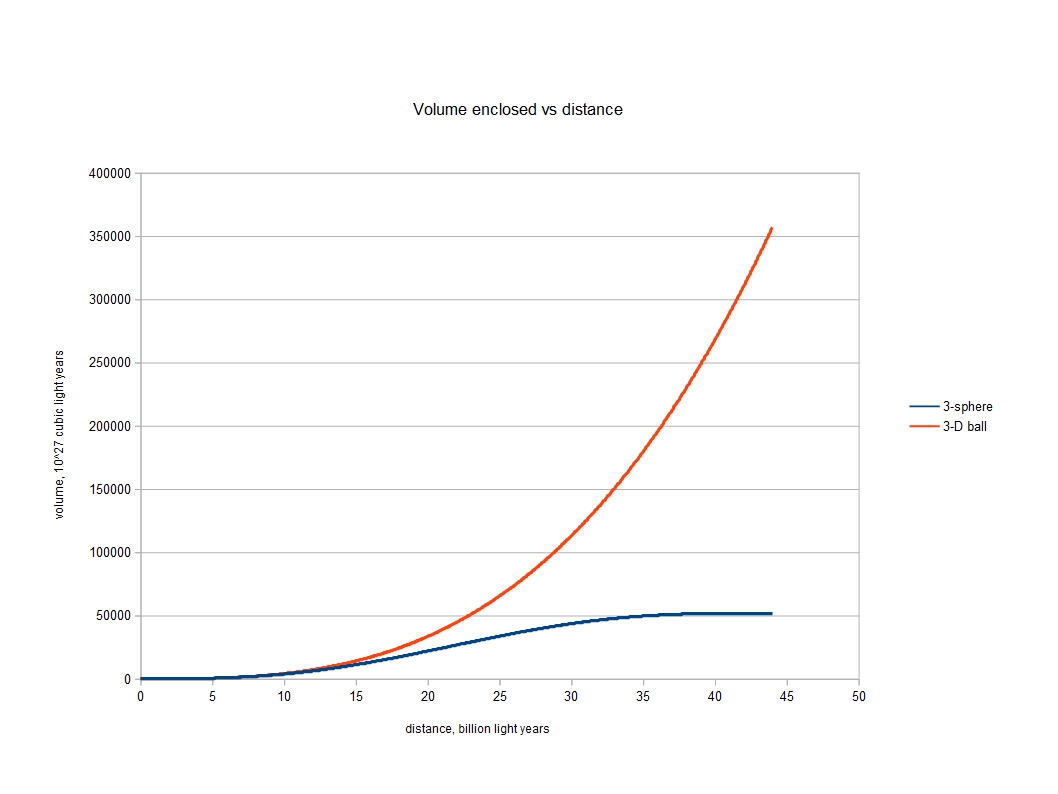

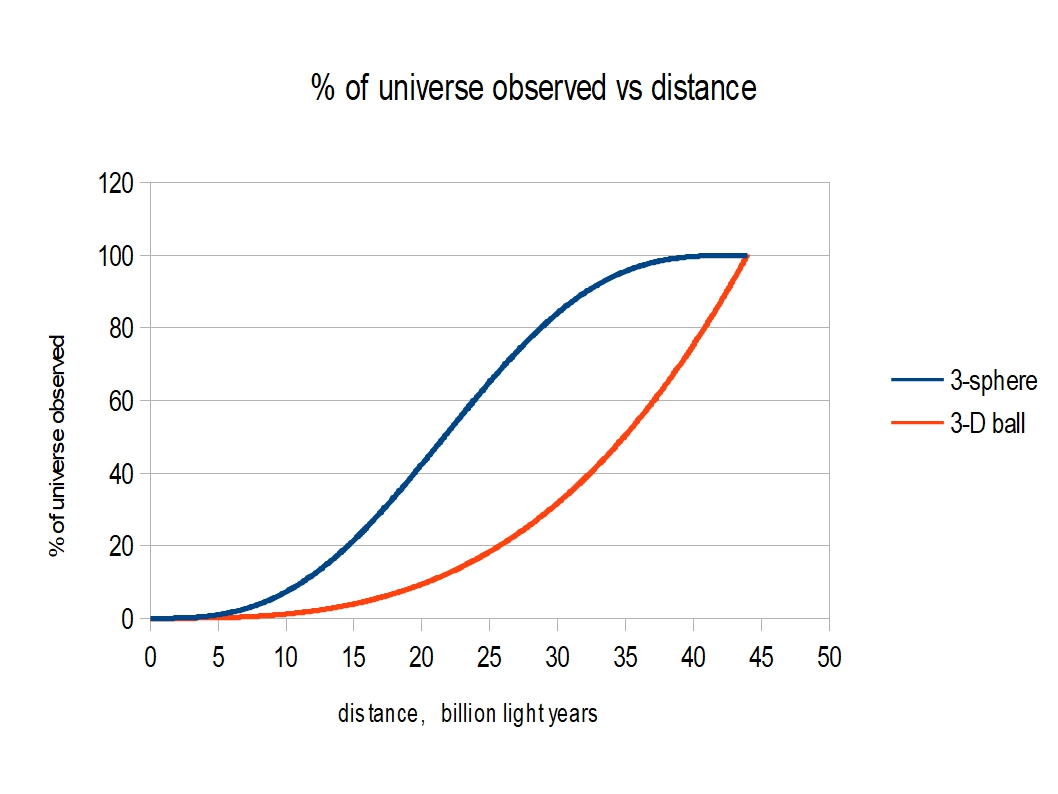

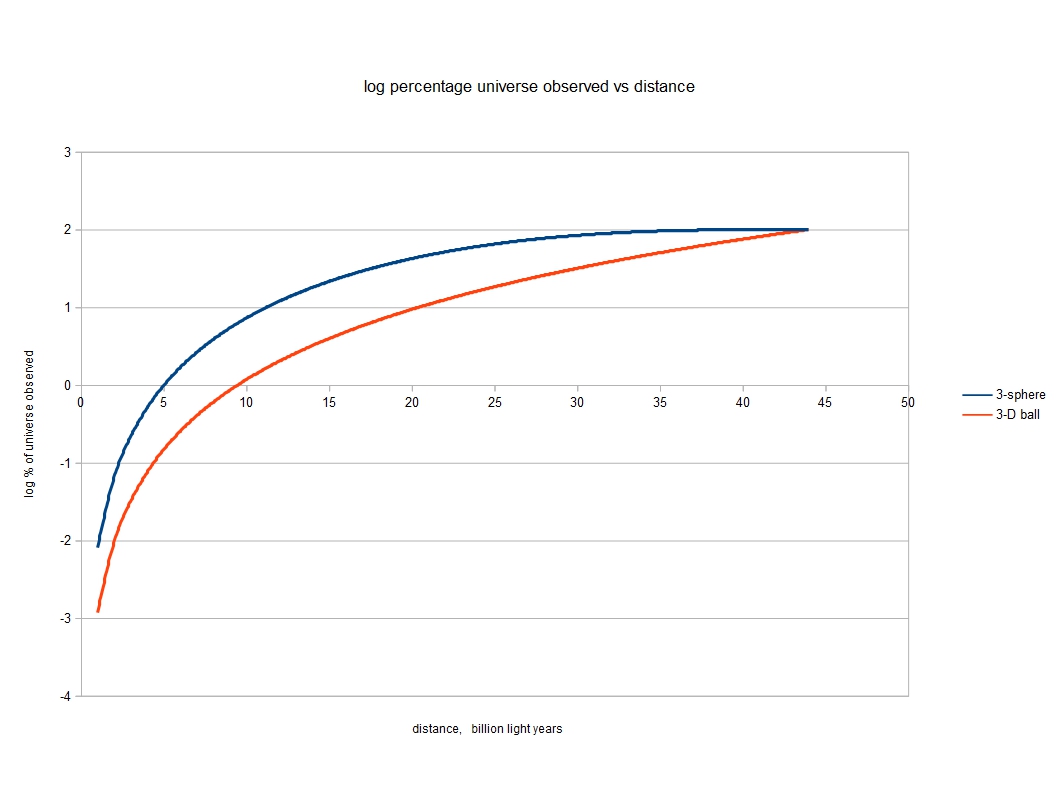

A 3-sphere is a 3-dimensional space so it has a volume. The volume of a 3-sphere is in fact

V = 2 π² r³

For our 3-sphere model, where r is 14 billion light years, this turns out to be 5.4 x 1031 cubic light years. A pretty large figure but then we expect the universe to be quite large. But now we know both the mass and the volume of the universe, it is a simple task to estimate its density. It is 1.9 x 10-27 kg/m³. The same website estimates a density for the universe of around 6 x 10-27 kg/m³ . I am not sure what volume was used but I doubt it was the volume of a 3-sphere (the volume of a 3-sphere is a little over four times the volume of a 3-dimensional ball of the same radius). The 3-sphere model produces an estimate for the density of our universe that is quite compatible with estimates from their observations currently being made by cosmologists.

More on the weight of the universe.

Some of you may have noticed from the formula given for the mass of the universe, that if its radius changes, so does its mass. More particularly if the radius increases, so does the mass. As the universe expands, the 3-sphere model predicts that it is getting heavier. But it is also getting bigger so this is equivalent to saying that space has mass. Most cosmologists would agree with this statement, though it is more usually couched in terms of energy (remember that energy and mass are interchangeable). The energy of free space is called the vacuum energy, the cosmological constant or dark energy, take your pick. It is quite easy to use the 3-sphere model to calculate how the mass of the universe increases as its volume does. It turns out that the density of the new volume being created is always exactly one third of the current density of the universe. This implies that though the university is getting heavier as it expands, its density is decreasing. With a little thought, that is what you might expect. From the escape velocity equation the universe gets heavier as it expands in proportion to its radius. But its volume is increasing in proportion to the radius cubed. Therefore you would expect the density of the universe (equal to mass/volume) to change in proportion to r / r3 which is r-2, (1/r2). According to the 3-sphere model, though the mass of the universe increases as it expands, the density is proportional to 1/r2, so it decreases as the universe expands.

The density of new space, at one third the current density of the universe, is 6 x 10-28 kg/m³. It is more normal to present this as energy per cubic metre. The value is 5.8 x 10-11 J/m³ (Joules per cubic metre). This value was higher in the past and is decreasing as the universe expands. The value of the vacuum energy is highly uncertain, but the value calculated here is highly plausible. It is a factor of 20 lower than what is generally believed to be the maximum permissible value.

STOP PRESS

I was initially surprised when I realised the universe must increase in mass as it expands but soon became quite comfortable with this since space does have mass due to its vacuum energy so why should new space not have new mass? However, this led me to resurrect an old idea of mine. As the universe expands, all objects move further apart (gravitationally bound objects do not but that does not alter this argument). This increases the gravitational potential energy of objects and ultimately of the universe itself. And since potential energy, like all energy, has mass according to Einstein’s equation, E=mc2, this means the mass of the universe must increase as it expands. After failing to see how to quantify this, I put the idea to one side, but, if the universe is a 3-sphere, it turns out to be surprisingly easy to make this calculation. So I will present the result first, with the details below in coloured text.

It turns out that exactly 50% of the increase in mass as the universe expands is due to the increase in gravitational potential energy. And since this has been happening since the moment of the big bang we must conclude that 50% of all of the mass of the universe is due to the mass of its gravitational potential energy. I initially thought it would be rather neat if all of the increase in mass was due to the increase in potential energy, but then I realised that this would mean that all of the mass in the universe would be due to potential energy, which would make no sense at all. But the figure of 50% is intriguing. It is not so far removed from the value of 70% for dark energy, required for a universe with accelerating expansion. A 3-sphere universe, however, is not accelerating and does not require dark energy.

The calculation for the increase in the mass of the potential energy as the universe expands, turns out to be surprisingly simple. But first, start with looking at the increase in total mass as the universe expands. As shown above this is

Mtotal = C² r / 2G

so the increase in total mass with radius, dMtotal /dr is as follows

dMtotal /dr = C² / 2G

Now consider one cubic metre of space. On average this will have a mass, m, equal to the total mass of the universe divided by the total volume, v.

m = Mtotal /v

= C² r / 2G v

There is a force due to the gravity from the rest of the universe acting on this cubic metre according to the formula

F = m M G / r²

M is the total mass of the universe, acting at its centre of gravity, the centre of the universe, at a distance equal to the 3-sphere radius of the universe. Substituting for m and M we get

F = C² r / 2G v . C² r / 2G . G / r²

= C4 / 4G v

Energy equals force times distance, so as the universe expands, the increase in energy due to gravity is given by

delta E = C4 / 4G v delta r, or

dE/dr = C4 / 4G v

This is the energy increase on one cubic metre of space as the universe expands. So to get the total increase in gravitational energy as the universe expands, multiply by the volume

dE/dr = C4 / 4G

And to get the change in mass, divide by C².

dMp.e./dr = C² / 4G

and

dMp.e. /dMtotal = ( C² / 4G) / ( C² / 2G) = 0.5

As the universe expands, the increase in the gravitational potential energy, expressed as mass, is exactly 0.5 times the increase in the total mass.

In the beginning

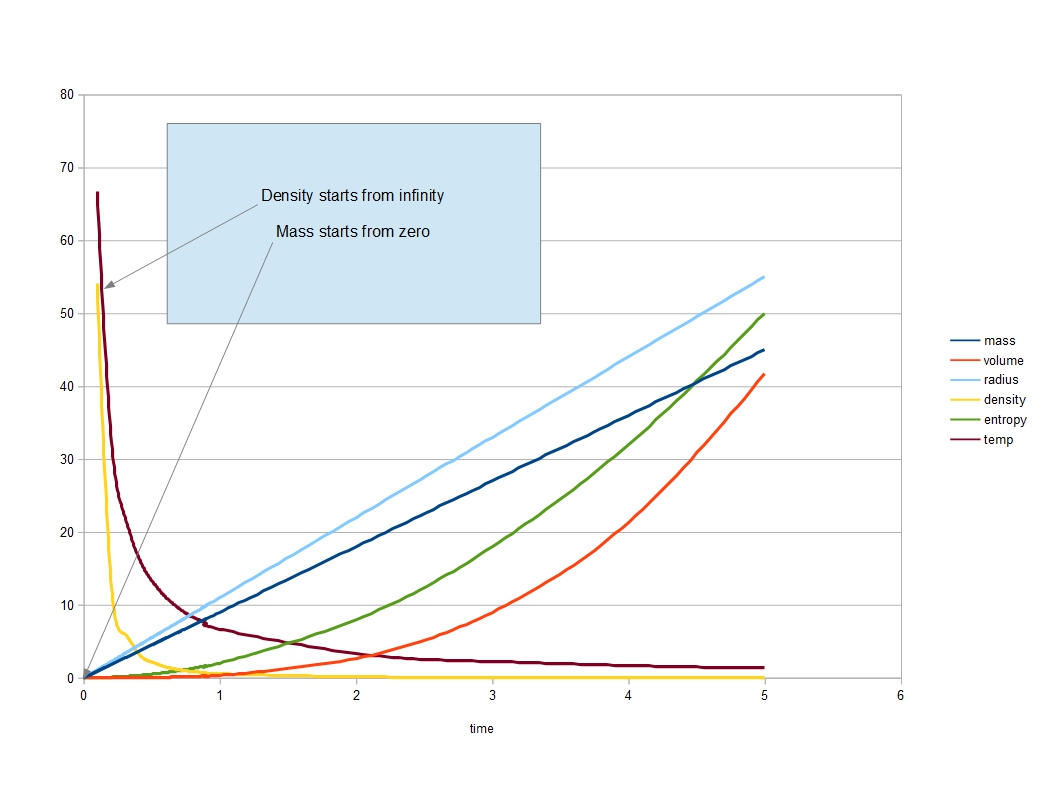

Now that we have a model of the universe it is impossible to avoid the temptation of winding it backwards to see what the big bang may have been like. Rather than trying to calculate any actual values I am simply going to se what happens to them as we wind our 3-sphere model backwards to zero time. Spoiler alert. Each of the parameters either falls to zero or rises to infinity.

The six parameters selected are radius, volume, mass, density, temperature and entropy. As the universe shrinks as we go back in time, the radius decreases in proportion to the time, a straight line, reaching zero at time zero. This is at the heart of the 3-sphere model. It may be meaningless to go all the way back in time to zero, because it is believed the laws of physics that we know, will break down, but that doesn’t really matter, we can still see where everything is headed.

The next parameter we can follow is volume, the red line. This also falls to zero in proportion to the radius cubed. And the mass of the universe, as shown earlier, the dark blue line also falls to zero, but this time in proportion to the radius. But because the mass falls more slowly than the volume, the density of the universe rises as the radius decreases. Most people expect the density of the early universe to be high, but according to the 3-sphere model it is rather odd. As the radius, volume and mass (which includes all energy) all fall to zero, which in total appears to represent nothing at all, the density rises to infinity. At zero time and radius, the density equals zero divided by zero, which mathematically is an undefined quantity, but it can be seen from the graph that it is definitely headed towards infinity. It is rather like the Cheshire cat in Alice in Wonderland, but in reverse. As the cat slowly disappeared, all that was left was its grin. Here as we go back in time, the universe disappears, at least its radius, volume and mass disappear, and all that is left is its density.

Maybe density is not the only thing left as the universe shrinks to nothing. I have shown temperature also rising to infinity. This is pretty much common sense. When you compress something it gets hotter, think of a bicycle pump. But perhaps common sense is not the best guide here, after all we are talking about the temperature of nothing. But there is one particular temperature that we can follow. This is the temperature of the Hawking radiation, named after Stephen Hawking. If you remember, when we used the escape velocity formula to calculate the mass of the universe, I said that this formula, when the speed is the speed of light, is identical to the formula relating the size of a black hole to its mass. Perhaps our 3-sphere is part of a black hole. And black holes have a temperature, due to Hawking radiation. The temperature of a black hole the size of our universe, is tiny, far smaller that the actual temperature of our universe, but according to the formula for Hawking radiation, the temperature rises as the black hole shrinks and rises to infinity just as a black hole shrinks to nothing. So for this reason alone, I think we can say that the temperature of our 3-sphere will be infinity at time zero.

There is one final parameter left, entropy. This is a parameter that many people, including myself, struggle with. There are a few things to say about entropy.

- Whenever anything changes, entropy always increases. Entropy can never decrease.

- Entropy is a measure of disorder. Disorder always increases. Houses never get tidier on their own. It is because there are far more ways of being untidy than there are of being tidy.

- But you have to consider the whole system. When a plant grows, order is being created, so locally, within the plant and its immediate surroundings, entropy is decreasing. But the entropy of the sun, which is providing the energy for photosynthesis, is increasing which outweighs the local decrease.

- Entropy is often equated to information. Google ‘Maxwell’s demon’ if you want more ‘information’ on this. Basically entropy is equivalent to the information missing to completely describe a system. If a system can be fully described then the entropy of the system, plus the information, is zero.

Actually I lied a little, earlier, when I gave a bicycle pump as an example of things getting hotter when you compress them. It is true that when you push on the pump, you compress air and it gets hotter. But when you pull back on the pump, you are expanding air, and it should get colder, which it does. But the cooling is never enough to compensate for the heating so overall the temperature does rise, and the reason is entropy.

I don’t want to digress too far into entropy but I do find it fascinating. Take a very simple system which has just has one property, such as a coin which can be heads or tails. If that is all you know, the coin can be in one of two states and the entropy is k log 2, a number between 0 and 1. More information is required to fully describe this system. But if you look at the coin and see that it is heads, then the coin can only be in one state, heads, and the entropy is k log 1, which is zero. There is now zero missing information.

So what is the entropy of our universe. It might seem obvious that as the universe shrinks and we get less mass and volume, we will get less entropy. Entropy will drop to zero along with the volume and the mass. But I’d rather not use common sense here. After all the situation is far from common. In our everyday universe entropy can only fall to zero at absolute zero temperature and we are talking about an infinitely high temperate at time zero. Instead I will fall back, once again, on black holes. According to Stephen Hawking and others, the entropy of a black hole is proportional to its surface area (I make no attempt to explain this rather bizarre concept!). Well OK. As mass falls into a black hole its associated entropy gets lost, which is not allowed, but in fact the black hole gets bigger, its surface area increases and so does its entropy. Overall, entropy does not get lost. On this basis then, as the universe reduces in size, its entropy reduces in proportion to its area. Since area falls in proportion to the radius squared, entropy is reducing in proportion to the radius squared, the same as the mass.

So entropy falls to zero at the moment of the big bang. This means enough information must exist at this point to completely describe the universe. There would seem to be two possibilities. The universe is certainly an enormously complex place. If zero entropy implies enough information to describe the universe as it is going to be, this would be almost unimaginably enormous. But it is also possible that at the moment of the big bang the universe is extremely simple, perhaps in a single state, such that no information is required to describe it. More and more information is required to describe the universe as it evolves (so there is more missing information) which is why entropy always increases.

Some loose ends

The extremely young universe

Many physicists believe space is not infinitely divisible, eg there is a smallest possible length, the Planck length. Associated with this is the smallest possible interval of time, the Planck time. Other properties, such as mass, also have a Planck value, although in this case it is not the smallest possible mass. These units are shown below

- Planck time 5.39 x 10-44 seconds

- Planck length 1.62 x 10-35 metres

- Planck mass 2.18 x 10-8 kilograms

If we start with the Planck time, 5.39 x 10-44 seconds, and let our 3-sphere universe expand at the speed of light for this length of time, it will have a radius of 1.62 x 10-35 metres, exactly equal to the Planck length and it will have a mass of 1.09 x 10-8 kilograms (around 10 micrograms) exactly one half of the Planck mass (it will be the Planck mass if we use Newtons formula rather than the Schwarzschild formula). This seems quite significant to me.

There is another illustration here. Some of you might feel a little unsure about the statement that the density of the universe was infinitely high at time zero. After all, the mass and volume were both zero and the density, 0/0, is undefined. But consider the Planck sized universe. It weighs only 10 micrograms. The volume however is roughly equal to the Planck length, 1.62 x 10-35 cubed, or 10-105 m, and the density is roughly 1097 kg/m3, a value almost unimaginably high.

A rotating universe

Our 3-sphere universe could be rotating. That could be very significant but I am not sure it changes much that we have discussed so far. Diverting away from this blog a bit, I have wondered whether rotation and angular momentum could be an alternative explanation for dark matter. Take our sun. It rotates every 25 days. If this rotation is slowing down then the angular momentum of its rotation would be converted into angular momentum of its path, rather like a David Beckham free kick. This might then be an alternative explanation to dark matter as to why our sun is rotating round our galaxy faster than it is supposed to be, according to Newton’s equations. I’ve tried my hand at calculating this and it seems the sun’s rotation is not fast enough to replace the need for dark matter. There are other possible sources of rotation. Galaxies rotate around galactic clusters and galactic clusters rotate around galactic superclusters, but neither rates of rotation seem sufficient. But if the universe itself were rotating? However dark matter also seems to be required to explain gravitational lensing so it probably does exist. In fact I have a candidate of my own, which I will add to the end of this blog. (Late addition, I no longer think my first candidate can work but I have come up with yet another candidate).

A changing speed of light

The model presented here for the universe is a 3-sphere expanding at the speed of light. I have assumed the speed of light is constant. The speed of light in a vacuum is constant as far as we know and for the vast majority of the life of the universe, empty space has been as near a vacuum as makes no difference. But this might not have been true in the extremely early universe. When the universe was very dense, the speed of light is likely to have been slower. Whether c in the equation for a 3-sphere universe should be the speed of light in a vacuum, a constant, or the actual speed of light appropriate to the age of the universe of interest, I do not know. It makes very little difference to most of what we have been discussing but I daresay it would make quite a difference to those trying to sort out the detail of what happened in the very first moments after the big bang. As an instance, as the very early universe expands, its density falls and the speed of light increases and this could become an additional contribution towards inflation.

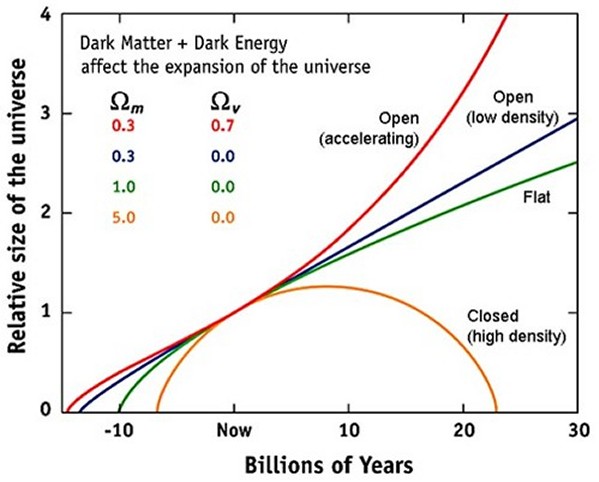

An accelerating universe

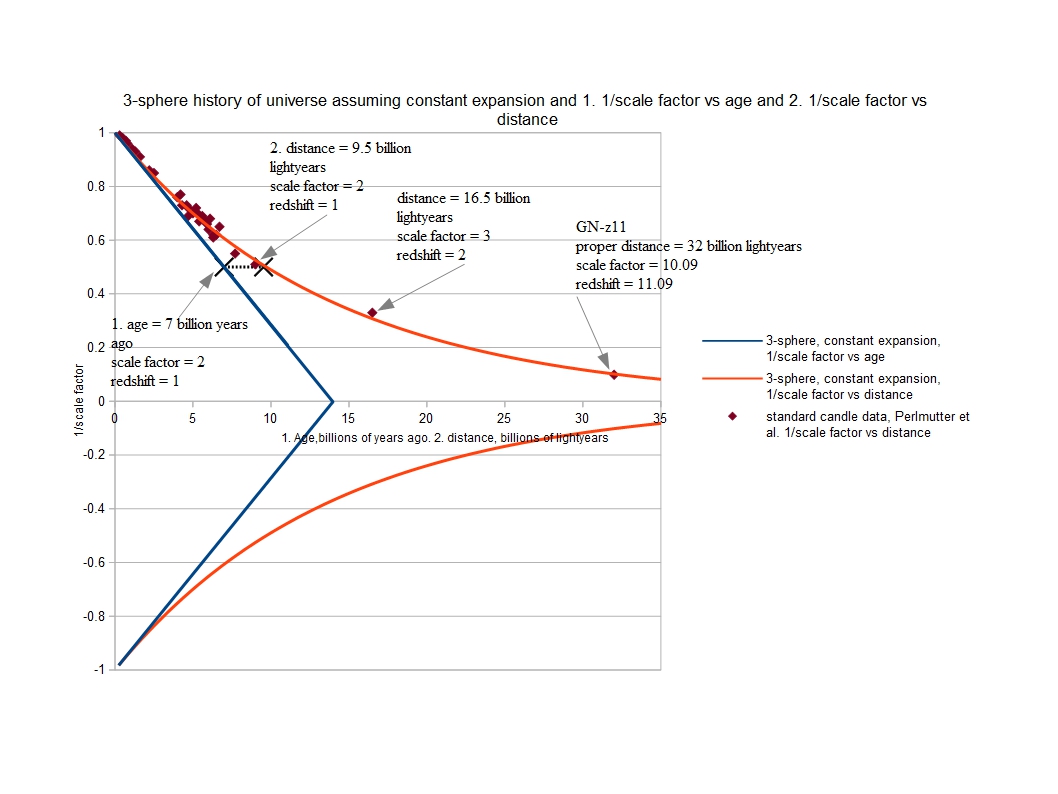

Some precise measurements made by astronomers over the last 20 years or so, Perlmutter et al, have apparently shown that the expansion of the universe has slowed down for the first 9 billion years or so of its existence, but after this for the last 4 or 5 billion years the expansion has been accelerating. Initially this seemed to be quite a problem for the model of the universe presented here with a constant rate of expansion. However, if you calculate the distance vs redshifts predicted by the 3-sphere model it is precisely as predicted by the Perlmutter data. The Perlmutter data only leads to an accelerating universe if the universe is flat, but of course a 3-sphere universe is not flat. This blog is getting rather long so for the details, visit this link. Perlmutter letter 9th Oct 2018.

But I can’t resist showing you the result. In the diagram below, the blue line shows our 3-sphere universe expanding at a constant rate for 14 billion years. The bottom half of this diagram is added simply because it emphasizes that this shows how the universe is expanding but we only need to concentrate on the top half. The red line is the distance in the present day universe to objects of a given red shift or scale factor. It is the distance around the outer circle in the ‘onion’ diagram. The brown diamonds are the observations made by Perlmutter et al, using supernovae type 1a as standard candles (the distance to GN-z11 has not been measured, it is an extrapolated value according to the standard model but it is intriguing to say the least that it fits so well with the 3-sphere model). The observations match the distances in our 3-sphere universe perfectly. But the Perlmutter data need not imply that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. The 3-sphere model is a simpler explanation.

My method of working tends to be directly with numbers using a spreadsheet. Because of this I missed something really elegant, pointed out to me by Andrew Ramsey. Andrew has also proposed a 3-sphere (or hypersphere) universe similar to that proposed in this blog, although he has concentrated on the possibility that as the universe expands it is the gravitational constant that gets bigger, not the mass. I still prefer the idea of the mass increasing, sorry Andrew. Let us look at our image of the expanding universe again.

Measure the distance to a galaxy in our universe, using eg one of Perlmutter’s standard candles. For example the point labelled R1 is 9.6 billion light years away. This is the distance as seen in our current universe and is the distance around the circle. If we divide this distance by the radius of the universe now, 14 billion light years, we get an angle, a, in radians. exp(-a) then equals the scale factor of the universe when the light seen was emitted from that galaxy. exp(9.6/14) equals 0.5. The universe was 0.5 times its current size (and 0.5 times its age, ie 7 billion years). And the red shift is exactly 1/0.5 -1, which is 1. A red shift of 1 at a distance of 9.6 billion light years is exactly what Perlmutter has measured. This relationship holds for all of the measurements made so far by Perlmutter and colleagues out to a red shift of at least 2. Galaxy GN-z11 is the most distant galaxy yet observed and has been given an extrapolated distance of 32 billion light years according to the standard model. With its red shift of 11 (hence its name) it conforms to this relationship perfectly.

Take another point, that labelled 22.14. The distance to that point in our universe is 44 billion light years. The angle made is 44/14 radians, which is pi. The scale factor of the universe when light left this point, when it was at the position marked ‘A’ is exp(-pi) which is 1/23.14 and at an age of 14/23.14 or 0.6 billion years, and the corresponding red shift is 23.14-1 or 22.14. No object has yet been observed at such a large red shift and so far distances have been confirmed only to even much lower red shifts (the microwave background radiation has a red shift of over 1,000 but I would not call this an object as such).

More on an accelerating universe.

When a photon leaves an observer, it departs at the speed of light and then it accelerates away. This may seem strange since surely the photon cannot travel faster than light. Due to the expansion of the universe, however, after say 1 billion years, the photon is further than 1 billion light years away from the observer. It certainly appears to have been travelling faster than the speed of light. If we follow a light ray backwards from the observer, B, in the present day universe, for 1 billion rears, the photon will be 13/14 times 1 billion light years from the observer. The photon appears to have been travelling slower than the speed of light. Move forwards for 1 billion years (not shown) and the photon will be 15/14 times 1 billion years from the observer; it certainly appears to have been travelling faster than the speed of light.

It is possible to calculate this apparent acceleration. It is 2 x 10‾¹¹ m/s². I suspect this may be the same as the apparent acceleration of the rate of expansion measured by Perlmutter et al. The problem with the standard model is that the universe is infinite, there is not an object as such that is expanding so it is difficult to calculate the equivalent value for the acceleration. It is possible to say, however, that in the 3-sphere model if we move backwards or forwards 1 billion years the speed of expansion decreases/increases by around 7%.

The diagram below shows the expanding universe (though not as predicted by the 3-sphere model). The top red line is according to the standard model, what Perlmutter’s data seems to be supporting (though it supports the 3-sphere model at least as well). I have not been able to obtain any numbers or formula for this line but just by eye it looks quite plausible that as you move backwards or forwards 1 billion years from ‘now’, the gradient of the line, equal to the rate of expansion, could change by around plus/minus 7%.

It looks quite plausible that the acceleration in the expansion rate of the universe according to the standard model is numerically the same as the apparent acceleration of a photon in the 3-sphere model.

A candidate for dark matter

When dark matter was ‘invented’ to explain why stars orbit their galaxies faster than they should according to Newton or Einstein (take your pick) I thought it was a bit lazy and that perhaps their was an alternative explanation. Others had similar views. But now dark matter also seems to be necessary to explain the details of gravitational lensing and also the details of how galaxies first formed in the universe. It seems that dark matter probably does exist. But despite almost heroic attempts (and expense) by the scientific community, the nature of dark matter remains a mystery. So here is a candidate. I would not say it is predicted by the 3-sphere model, but I would say it seems to be allowed. And it does explain why it has been so hard to find. Basically I believe dark matter could be light (pun not intended but of course noticed). So why have we not seen it. Well it could be electromagnetic radiation (as light is) of an enormous wavelength, of the order of millions, perhaps tens of millions, of light years. I cannot think of any method by which we could detect such light but perhaps others can. So where do these long wavelength photons come from. They come from the early universe. There is no doubt that the early universe was teeming with photons. In fact the very early universe was pure radiation, radiation being photons. Now imagine the very early universe, when it was say 10-44 seconds old. Any photon from then, if it made it through to our present day universe, would be red shifted by a factor of 1060, and its wavelength stretched by this same factor, 1060 an absolutely enormous wavelength no matter how small it might have been to begin with. Presumably as the universe grew, the energies of the photons would reduce and there wavelengths would increase. So even as the red shift reduces, the present day wavelengths of these early photons remains enormous. So far so good. It seems rather plausible that there could be huge numbers of extremely long wavelength photons in our universe. But there is a problem. As the universe expanded it goes through phases when it is believed to have been opaque to electromagnetic radiation. In which case photons from the very early universe would not make it through to today. But what if the wavelengths of photons had already red shifted to enormous lengths before these opaque phases appeared. Perhaps the universe would not have been opaque to such huge wavelength photons. Think of bricks. These are normally thought of as opaque but radio waves with wavelengths of just a few metres have no trouble penetrating bricks. We are talking about photons with wavelengths that are a significant fraction of the size of the universe. I am not sure these would be absorbed.

So it seams feasible that our universe is filled with extremely long wavelength photons, with wavelengths a significant fraction of the size of the universe. If there were enough of them, their energy would be equivalent to the mass of dark matter that is required to exist. There is however another problem, but with a proposed solution. For dark matter to fulfil its required roles it is required that it should clump under the force of gravity, in much the same way that ordinary matter clumps into galaxies and stars. Dark matter that behaves like this is known as cold dark matter. Radiation can provide the mass required of dark matter, but it does not clump. Radiation would in fact be hot dark matter and not meet all of the requirements of dark matter.

However radiation could fulfil the requirements of dark matter another way. Extremely long wavelength light could set up an interference pattern in the universe with peaks separated by millions or tens of millions of light years. The radiation, and its associated gravity would appear concentrated at these peaks and be able to act as the required seeds for galaxy formation and in the other ways required of dark matter.

There might appear to be a problem here. Just because a photon’s electromagnetic field might participate in an interference pattern, its gravitational field need (or would) not. But photons are massless objects. Any mass they possess is entirely due to their energy and that energy is electro-magnetic. So peaks and troughs (nodes) in the electro-magnetic field would correspond to peaks and troughs in the associated gravitational field.

There is another problem though. If the amount of dark matter required in a galaxy is around 5 times the amount of ordinary matter, and this is extrapolated to the whole universe, it means at every node where there is a concentration of electromagnetic energy, there would need to be a galaxy. This means that galaxies would be very evenly distributed throughout the universe, and this is far from the case. A totally different candidate for dark matter is presented later in this blog.

Final note

So far I have not attempted to illustrate a 3-sphere, and I think this blog is long enough. But if you want some more thoughts on a 3-sphere, go to thoughts on a 3-sphere. And if you want to see a video of a supercube go to – currently this site does not support videos. Try instead Tesseract cartoon

It’s never the final note!

One of the great attractions of the 3-sphere model is its simplicity. To most of us, who are not that accomplished at maths, some of the calculations presented in this blog may appear daunting, but believe me, they are a piece of cake compared to the calculations in general relativity required by cosmologists to use the standard model. A case in point is the supposed dark energy and the supposed accelerating expansion of the universe.

It is reasonable to ask ‘what is driving the expansion of the universe’? It might be reasonable to just accept it as a fact, but then it’s good to ask questions. Most cosmologists believe the force of gravity slows down the expansion of the universe. If this were the only force in play, the expansion of the universe would eventually stop and it would start to contract. But there is another force. This is an outward force due to the pressure of dark energy (in the standard model. In the 3-sphere model we have already seen that the sum of gravitational potential energy and kinetic energy is similar to the amount of dark energy required by the standard model).

Dark energy seems very mysterious and its pressure seemed more mysterious still until one day I had an insight – energy density and pressure are the same thing, at least they have the same units. Pressure is Newtons/m² and energy density is Joules/m³. And since a Joule is a Newton.metre and a m³ is a m².metre you can see that the units are identical.

I would encourage all of you who are interested in this sort of topic to carry out dimensional analysis. It is extremely simple and leads to all sorts of insights and is vital for checking formulae (the dimensions must match). The units relevant here are as follows

Force, mass x acceleration, M L T¯²

Pressure, force per square metre M L T¯² L¯² = M T¯² L¯¹

Energy, force times length M L T¯² L = M L² T¯²

Energy density, energy per cubic metre M L² T¯² L¯³ = M T¯² L¯¹

You can see that pressure and energy density have the same units.

In the standard model there is an equation of state

p = w ρ

where p is the pressure, ρ is the energy density and w is a dimensionless constant, which should be between -1 and 1, but generally between -1 and 0. Cosmologists run computer models to determine what value of w best fits our universe with its supposed accelerating expansion, and come up with a value of -1. The minus sign implies that the force produced by this pressure is the opposite sign of that produced by gravity, as you might expect. The balloon analogy continues to be good. In a balloon there is a pressure driving expansion and a surface tension, driving contraction. Normally these balance. However, in the standard model there seems to be a problem. It is said to be gravity acting on dark energy which drives expansion. This is presumably because in an infinite universe there is no surface for the pressure due to its energy density to push against.

In the 3-sphere universe, however, the expansion rate is a constant, the speed of light. It is reasonable to assume that, with no acceleration, the force acting on the universe is zero (Newton’s 1st Law). That is the inwards force due to gravity exactly counters the outwards force due to the energy density. And since in the 3-sphere model we know the total mass and the total energy and the volume, 2 pi² r³ and the area, 6 pi² r², by equating the total force due to gravity to the total force due to pressure, w can be calculated. If we consider just the potential energy, equal to half the mass of the universe, w is -1/3. If we add in classical kinetic energy of ½mc², equivalent to a universe which is 66% energy and 33% matter, w falls to -1/4 and if instead we assume a relativistic energy of motion of mc² , equivalent to a universe that is 75% energy and 25% matter, w falls further to -2/9. For comparison, putting w=-1/3 into the standard model results in a ‘curvature dominated universe with a constant rate of expansion’ which sounds very much like the 3-sphere model.

Here is the calculation.

First, calculate the total force on the universe due to gravity. Remember, each point in a 3-sphere is the same distance, r, from the centre. So the force between any kg and the mass of the rest of the universe acting at its centre of gravity, is

f = G x 1 x m/r² Newtons

And the mass of the universe, m, is

m = c²r/2G kg

Combining these, gives

f = G x 1 x c²r/2G x 1/r² Newtons

Multiplying this by the total mass of the universe (again) gives the total force due to gravity.

f gravity = G x c²r/2G x c²r/2G x 1/r² Newtons

=c² x c² /4G Newtons

If, for the moment we only consider the potential energy in the universe, whose mass equivalent is equal to 50% of the total mass.

total potential energy = c²r/4G x c² Joules (using E = Mc²)

And the potential energy density, ρ, equals the total potential energy divided by the volume.

ρ = c²r/4G x c² / (2 x pi² x r³)

Using the equation of state

p = w x ρ Newtons/m²

= w x c²r/4G x c² / (2 x pi² x r³) Newtons/m²

If this pressure is multiplied by the total area of the universe, 6 pi² r², we get the total force due to the energy pressure.

f pressure = w x c²r/4G x c² x 6 pi² r²/ (2 x pi² x r³) Newtons

If f gravity is equal to f pressure, then